The potential for a consequential disruption in China's supply chains appears to be vastly under-appreciated.

Despite the current drop in stocks (less than 1.5% as this is written), there's a tremendous reservoir of complacency about the economic and financial impact of the coronavirus epidemic. The zeitgeist reflects an implicit confidence that the coronavirus will blow over like the SARS scare a few years ago and the impact on the global economy will be essentially zero.

Have all the risks already been fully discounted? Here are some of the reasons why the assumption that this will have little effect on the U.S. economy and stock market may be misguided:

1. Patient One (the first reported case of 2019-ncov) on 31 December was unlikely to be the person in which the mutation enabling person-to-person contagion occurred. The latest genetic analysis suggests the virus first mutated into its present form sometime between late October and late November.

It's thus highly likely the virus had already been spreading for at least a month before 31 December. The symptoms of this new virus are not that different from typical flu strains, so why would authorities spend the time and money searching for a novel flu in a patient? The only reason authorities become involved would be a cluster of flu/ pneumonia patients dying.

Hundreds of thousands of people die of the flu every year, between 12,000 and 50,000 in the U.S. alone, so the death of a patient with flu-like symptoms is not uncommon enough to trigger an official investigation.

This line of reasoning suggests there was already an expanding pool of virus carriers long before officials discovered the new virus and began acting to limit its spread.

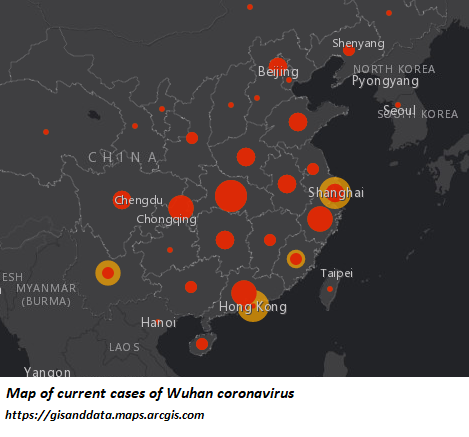

If this is the case, then the virus may have spread outside Wuhan before officials reacted.

2. This virus is a new type, and this makes it especially dangerous as humanity may have limited immunity to viruses that are sufficiently different from existing variations.

There are several bits of evidence that this novel flu is both contagious and dangerous. One is that health workers have caught the flu from patients despite all precautions and anecdotal evidence that the disease has spread from one family member to everyone else in the household.

The other is the relatively high death rate. Based on data from Chinese authorities (likely incomplete) , about 3% of the patients have died. The great flu pandemic of 1918-19 killed about 2.5% of its victims, and since it was highly contagious, it's estimated 50 to 60 million people died in that pandemic--often young healthy people.

3. The incubation period for this flu may be up to 14 days, and someone who has it may be asymptomatic (display no symptoms) for 5 or 6 days. This means screening passengers for fever is essentially useless.

Even more alarming, the new virus doesn't always cause a fever, making screening for fever even less effective.

Despite these data points, the American populace is being assured that screening is effective and so it's perfectly safe to travel as usual. This complacent confidence appears to be unfounded.

4. The Chinese populace is highly mobile within China and the world. Hundreds of thousands of Chinese work in other nations, and a significant percentage of these offshore workers returned home for Lunar New Year and will be returning to their jobs in the U.S., Europe, Africa, Southeast Asia, the Mideast, etc. next week.

To assume that none of these returning workers are asymptomatic carriers of the flu is a stretch.

5. Researchers are busy developing a flu shot to offer some immunity, but if this virus is virulently contagious, the question becomes: can authorities outrace the spread of the virus? Realistic estimates of how long it will take to develop and test a vaccine are 6 to 7 months, and that's if everything works perfectly, i.e. the virus doesn't mutate, etc. Producing hundreds of millions of doses and administering the vaccine to hundreds of millions of people will take additional time.

6. The implicit model for this coronavirus in the mainstream is SARS, which was isolated and contained. But this new virus may be much more contagious and so the relatively rapid and successful isolation of SARS may be a misleading model.

7. Authorities seem to prioritize "don't panic" messages, as if fear of this flu is irrational. But fear of a risk that cannot be assessed with any confidence is entirely rational. The smart strategy is to lay low and wait for more evidence on the nature of the risk.

8. The potential economic impact of this virus is grossly underestimated. The Chinese economy is particularly vulnerable now for a number of reasons. In essence, all the low-hanging fruit of rapid development have been picked, and adding more debt to boost building and consumption is no longer as effective now that debt has soared.

The world has depended on China's skyrocketing consumption for growth for the past 30 years. Should China's economy actually contract due to the knock-on effects of the virus, the global economy will soon follow.

How fear triggers a domino-like effect in an economy is poorly understood. In an economy that's already teetering on recession, quarantines, disruption of travel and commerce and a generalized "circle the wagons" response to uncertainty will push the precarious economy over the cliff.

Once tourists cancel trips, incomes plummet and businesses are forced to close. There's no guarantee that they will re-open after months of recession.

If you fear catching a potentially life-threatening flu, you're unlikely to go shopping for a new car or furniture; you'll put that off if at all possible.

Then if you read about layoffs and recession, you decide the car and furniture can wait indefinitely.

This is how the transition from complacency and confidence to fear and caution ripples through the economy, as the initial impact unleashes knock-on effects that increase caution which then reinforces reduced spending and investment.

9. Confidence in the truthfulness and effectiveness of authorities is already low in China, and this loss of confidence will likely spread to other nations as people awaken to the authorities' obsession with "keeping the economy going" by discounting the risks with false assurances that "everything is under control."

When people realize everything is not under control and they've been misled to grease the wheels of commerce, the legitimacy of the state may come into question: if they downplayed the flu, putting me and my family at risk, why should I trust them about anything else? The epidemic has the potential to trigger a political crisis as well as a severe economic slump.

10. The potential for a downward spiral of confidence is high as authorities will be pressured to increase their reassurances that all is well at every new wave of evidence that the virus is spreading despite their efforts. Doubling down on "don't panic" as the virus spreads will eventually backfire and unleash the very panic they feared.

11. Global stock markets are at all-time highs or near-term highs, on the euphoric belief that central bank stimulus will push stocks higher essentially forever. The virus has to potential to refocus attention on sales, profits and future risks, and that could change the general mood from complacent confidence to uncertainty, which is Kryptonite to market confidence.

The virus might be the needle that will pop all the speculative bubbles, regardless of central banks' stimulus.

12. History suggests that this virus may rise in two waves. The initial wave may die down and everyone sighs with relief, assuming it's like SARS: everything's fixed, risk is back to zero. Restrictions are eased, travel bans lifted, etc. Then the second and much more virulent wave rises, catching everyone by surprise.

13. The potential for future mutations which increase the lethality of the virus are not being factored into current risk assessments. Assuming the virus will retain its current configuration is a leap of faith.

The potential for a consequential disruption in China's supply chains appears to be vastly under-appreciated. Again, the working assumption is that any disruption will be temporary and everyone in China will be back to work as usual in a few weeks. The market has yet to discount the possibility that China's supply chains will be disrupted for months, with all the ripple effects that would generate throughout the global economy.

The market also has yet to discount the possibility that China's consumption could crater (buying an iPhone 11 is no longer a priority, etc.) and knock-on effects in its currency and debt markets could disrupt global financial markets, potentially triggering insolvencies in overleveraged companies not just in China, but in the developing and developed economies as well.

While it's too early to predict global depression, it's also too early to predict a rapid return to pre-epidemic normalcy.

Here are some informative science-based links on the coronavirus, courtesy of longtime correspondent Cheryl A.:

DNA sleuths read the coronavirus genome, tracing its origins and looking for dangerous mutations

My recent books:

My recent books:

Audiobook edition now available:

Will You Be Richer or Poorer?: Profit, Power, and AI in a Traumatized World ($13)

(Kindle $6.95, print $11.95) Read the first section for free (PDF).

Will You Be Richer or Poorer?: Profit, Power, and AI in a Traumatized World ($13)

(Kindle $6.95, print $11.95) Read the first section for free (PDF).

Pathfinding our Destiny: Preventing the Final Fall of Our Democratic Republic ($6.95 (Kindle), $12 (print), $13.08 ( audiobook): Read the first section for free (PDF).

The Adventures of the Consulting Philosopher: The Disappearance of Drake $1.29 (Kindle), $8.95 (print); read the first chapters for free (PDF)

Money and Work Unchained $6.95 (Kindle), $15 (print) Read the first section for free (PDF).

If you found value in this content, please join me in seeking solutions by becoming a $1/month patron of my work via patreon.com.

If you found value in this content, please join me in seeking solutions by becoming a $1/month patron of my work via patreon.com.

NOTE: Contributions/subscriptions are acknowledged in the order received. Your name and email remain confidential and will not be given to any other individual, company or agency.

Thank you, Bengen Financial Services ($50), for your superbly generous contribution to this site -- I am greatly honored by your support and readership.

|

Thank you, Robert T. ($5/month), for your exceedingly generous subscription to this site -- I am greatly honored by your support and readership.

|