"Too Big to Care" and the Illusion of Choice

In a functional economy with real competition and transparency, every one of these cartel-corporations would be driven out of business by their 'too big to care' incompetence.

We've all heard of Too Big to Fail, a description of the consequences of consolidating capital and power in a few corporate entities, the net result of which is monopolies and cartels becoming so large that their collapse would send the entire economy into a crisis without easy solution, as the void left cannot be filled by competitors because there are no competitors.

Given the risks generated by this consolidation of capital and power in cartels, the federal government and central bank had to bail out these systemically critical corporations in 2008, regardless of the cost or political precedent being established.

One would be forgiven for reckoning that the first thing the federal government would do post-meltdown was break up the Too Big to Fail entities as an unacceptably dangerous source of systemic risk. But the Central State did nothing of the sort, and the dominant firms in every sector of the economy have continued consolidating by snapping up competitors and start-ups and merging with other giants.

Everywhere we look, a few firms dominate each sector--the perfection of state-cartel-capitalism in which the core dynamics of open markets--competition and transparency--have been suffocated as obstacles to expanding profits and power. Eliminating competition and transparency is the unstoppable logic of increasing profits by any means available, for eliminating competition and transparency are the lowest-risk ways to increase profits without bothering to increase productivity or quality.

This consolidation into quasi-monopolies and cartels has moved from too big to fail to too big to care: these companies now occupy the commanding heights of the economy and so they have no incentive to improve quality and durability or seek efficiencies that can be passed on to customers. Rather, they have every incentive to reduce quality and durability to boost profits via planned obsolescence and disregard for customer service.

Cory Doctorow has performed distinguished public service in revealing the endless chicanery corporations pursue to cloak their stripmining of customers, customers with no alternative other than another member of the cartel that offers the same low quality, the same products and the same prices.

This is the sweet spot for profitability: customers have only the illusion of choice and the chicanery of too big to care is well hidden. Once the customer has no real choice, or they're now dependent on or addicted to a product or service, then prices can be jacked up and quality can fall off a cliff to boost profits, with no blowback.

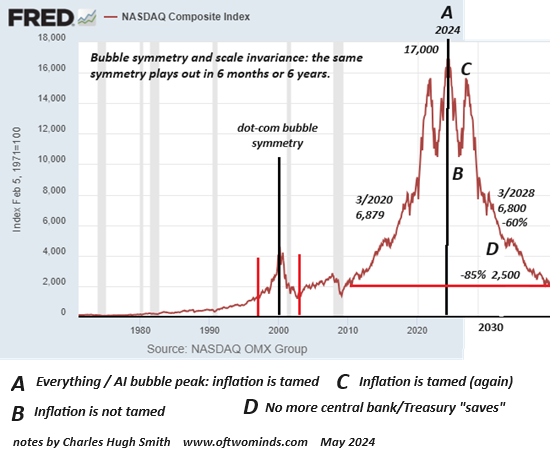

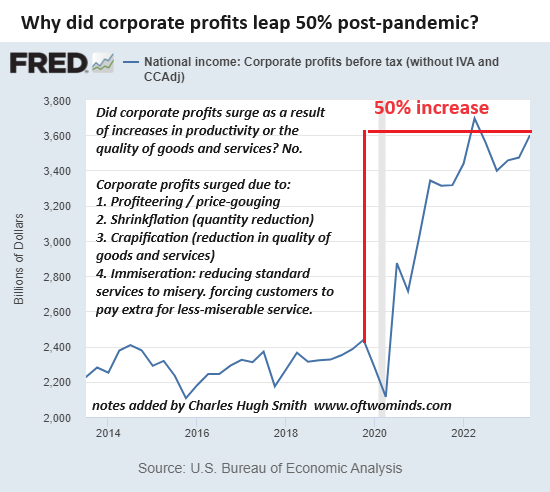

Here is a chart of U.S. corporate profits. Note the dramatic increase. If we ask "did profits soar 50% because corporations boosted productivity and quality by leaps and bounds or were they just too big to care?"

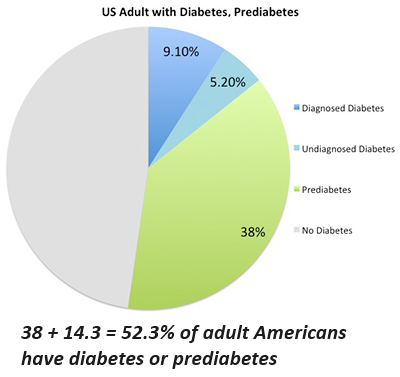

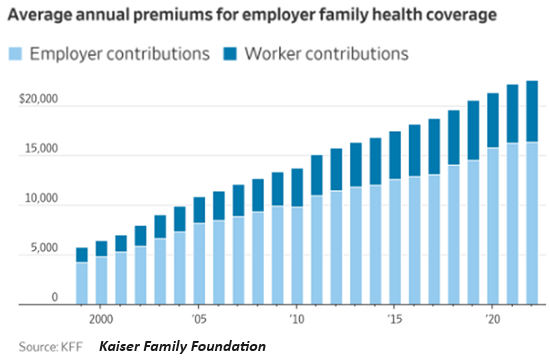

Consider the sector that is almost 20% of the entire economy: healthcare. Here is a chart of healthcare insurance costs. Do we really have a choice of healthcare and insurance? No. We get the same overpriced meds, long wait times, bankruptcy-triggering costs and abysmal mental-health care everywhere.

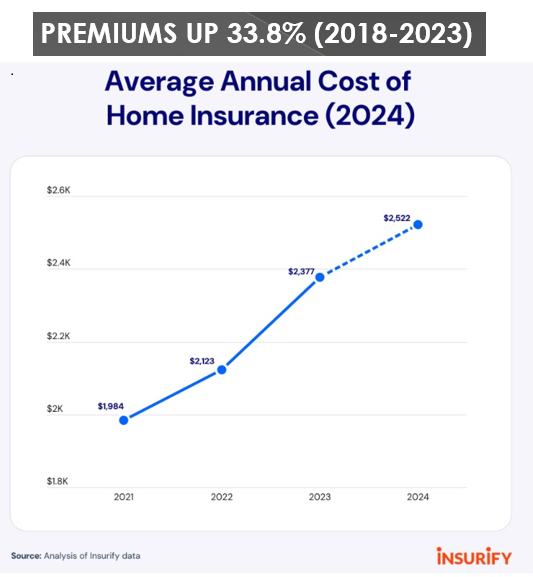

Speaking of cartels, consider the rest of the insurance industry. Prices rise, policies are cancelled, coverage is reduced, and where's the competition?

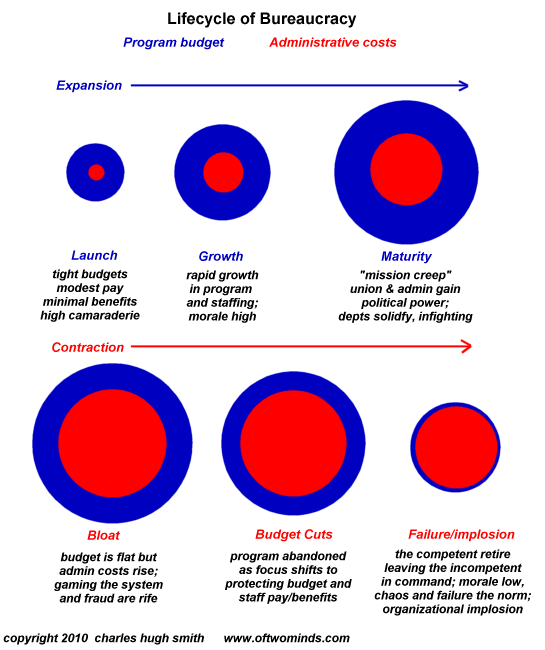

The government is of course the classic monopoly, and many state agencies are equally too big to care. I've posted my chart of The Lifecycle of Bureaucracy many times in the past 14 years, and if my own experience is any guide, the dynamics of too big to care in the public sector have increased in step with corporate cartels.

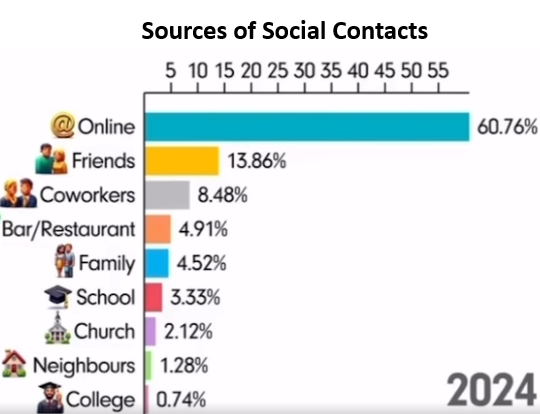

Consider tech. Does any "choice" actually eliminate malicious web traffic, or offer a device that lasts a decade rather than an obsoleted-brick that must be replaced every few years, or any service that doesn't collect the same quantity of user data to sell for immense profits?

The chicanery of monopolies and cartels is literally endless: dynamic pricing to squeeze a few dollars more out of customers trapped into using different versions of too big to care Addiction Capitalism, rusting "stainless steel" that I call stainless steal, and thousands of fines and settlements for corporate malfeasance, which you can review at your leisure in the remarkable data base of

Corporate Fines and Settlements from the early 1990s to the present compiled by Jon Morse.

Can we risk being honest about all this? Or does the whole house of cards collapse if we're actually honest about too big to care and the illusion of choice? The problems here are scale and concentration of capital and power: once any entity, private or state, reaches a scale and consolidation of resources / power that leaves customers / citizens no real choice, no real feedback / pushback and no real transparency on the inner workings of too big to care, then the system is ripe for collapse not from externalities but from its intrinsic instability.

Do we have any real choice in Department of Motor Vehicles, appliances, or anything else? Sure, there are dozens of toothpaste options, but we all know these are merely marketing gimmicks. The "alternative healthcare" brand is owned by a corporate conglomerate.

There is literally no bottom in the too big to care abyss. I'll share one example from my own life to illustrate this; you will no doubt have your own. The electronics in our crumbling Samsung range (rusting "stainless steel," etc.) finally failed after a few brief years of service, so we bought a new GE range from Home Depot, largely because this model was in stock.

GE shipped the new range with a defective thermostat that never worked. GE didn't care, and neither did Home Depot, which carefully refuses any warranty responsibility for the appliances they sell. When we called GE to honor their warranty and send a repair tech, the process was pre-Soviet-collapse painful--hours squandered trying to get a response via phone, online chat, emailing, none of which produced any timely results. We finally reached a staffer who took our address and scheduled a tech visit.

The day of the service call arrived and the tech texted us that he's on the way--to our address of ten years ago, 2,500 miles away in another state. After more wasted time, the customer service staffer we finally reached said their system was buggy and updating addresses generally failed.

In a functional economy with real competition and transparency, every one of these cartel-corporations would be driven out of business by their too big to care incompetence. Instead, we all move from one form of extortion and indentured shadow work to the next, regardless of sector or whether it is public or private.

Don't complain, it could be worse. "I am altering the deal, pray I don't alter it any further."

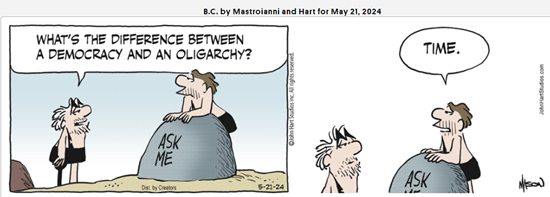

And what does too big to care and the illusion of choice do to democracy? In time, it transforms the republic into a state-corporate oligarchy.

New podcast:

Seeking a Culture of Honor and Integrity with Emerson Fersch and Amy LeNoble (59 min)

My recent books:

Disclosure: As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases originated via links to Amazon products on this site.

The Mythology of Progress, Anti-Progress and a Mythology for the 21st Century print $18, (Kindle $8.95, Hardcover $24 (215 pages, 2024) Read the Introduction and first chapter for free (PDF)

Self-Reliance in the 21st Century print $18, (Kindle $8.95, audiobook $13.08 (96 pages, 2022) Read the first chapter for free (PDF)

The Asian Heroine Who Seduced Me (Novel) print $10.95, Kindle $6.95 Read an excerpt for free (PDF)

When You Can't Go On: Burnout, Reckoning and Renewal $18 print, $8.95 Kindle ebook; audiobook Read the first section for free (PDF)

Global Crisis, National Renewal: A (Revolutionary) Grand Strategy for the United States (Kindle $9.95, print $24, audiobook) Read Chapter One for free (PDF).

A Hacker's Teleology: Sharing the Wealth of Our Shrinking Planet (Kindle $8.95, print $20, audiobook $17.46) Read the first section for free (PDF).

Will You Be Richer or Poorer?: Profit, Power, and AI in a Traumatized World

(Kindle $5, print $10, audiobook) Read the first section for free (PDF).

The Adventures of the Consulting Philosopher: The Disappearance of Drake (Novel) $4.95 Kindle, $10.95 print); read the first chapters for free (PDF)

Money and Work Unchained $6.95 Kindle, $15 print) Read the first section for free

Become a $3/month patron of my work via patreon.com.

Subscribe to my Substack for free

NOTE: Contributions/subscriptions are acknowledged in the order received. Your name and email remain confidential and will not be given to any other individual, company or agency.

|

Thank you, Sudheer B. ($50), for your magnificently generous subscription to this site -- I am greatly honored by your steadfast support and readership. |

Thank you, Keith ($7/month), for your superbly generous subscription to this site -- I am greatly honored by your support and readership. |

|

|

Thank you, John K. ($7/month), for your marvelously generous subscription to this site -- I am greatly honored by your steadfast support and readership. |

Thank you, Steve S. ($7/month), for your splendidly generous subscription to this site -- I am greatly honored by your support and readership. |