Long Cycles: Cheaper Goods, Costlier Capital, Income Disparity Increases

Welcome new readers. It seems a few thousand new-to-OTM inquisitive souls happened upon the site in the past few days--I hope the content and reader essays keep you coming back. Here is our RSS feed; archives are in the right column, other goodies are in the menu at the top of the page. I received many emails--thank you--and it will take me a few days to catch up. I appreciate your patience.

Truly great books provide a treasure trove of insights. One such analysis is The Great Wave: Price Revolutions and the Rhythm of History by David Hackett Fischer (sent to me by longtime correspondent Cheryl A.)

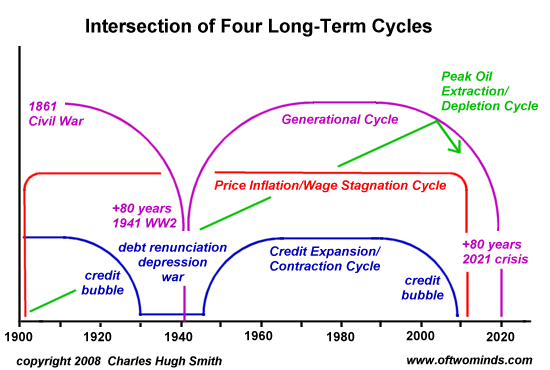

I have visually displayed Fischer's Price Wave along with three other long-term cycles: oil depletion (Peak Oil), generational (4th Turning) and Kondratieff (credit expansion and renunciation/contraction).

What else can we mine from Fischer's deep-history analysis? If history echoes, which it tends to do because human nature remains firmly stuck in Version 1.0 of Homo sapiens sapiens, then we can expect these long-wave trends to continue through at least 2021 (the expected full-blown epochal crisis/opportunity point), if not longer:

1. Manufactured goods stay cheap in terms of purchasing power. As far back as the 14th and 16th centuries, during long-term economic declines the cost of manufactured goods like nails stayed flat or decreased while the cost of food and capital steadily rose for decades.

Could this pattern repeat in the decades ahead? I would say yes for one reason alone: overcapacity. Those of you who follow consumer prices of manufactured goods (and who doesn't?) know there are two competing forces at work in manufacturing costs: the rising input costs of commodities and oil/energy, and the intense global overcapacity and price competition.

It comes down to this: everybody is getting into everybody else's business. What was once the reserve of high-tech manufacturing bases like Japan (think flat-screen monitors and TVs) is now made in Korea, China and elsewhere. As a result, the market is quickly glutted with oversupply and prices plummet to to the point where profits are negligible or negative.

Karl Marx explained this mechanism well in the 19th century. He was wrong about a lot of things, but Marx captured the dynamic of capitalist manufacturing rather well: any profitable venture attracts competitors, production skyrockets to meet demand, then exceeds demand. Prices drop, manufacturers exit or close, and "monopoly capital" takes over the remaining production, forming either a monopoly or a oligopoly which enables profits by constraining supply and/or fixing prices.

This was the case with The Big Three automakers before the coming of Japanese competition. In terms of pure monopoly, look no further than your cable TV/Internet provider, as in most areas there is only one choice. This goes a long way toward explaining why internet and cable prices in the U.S. are so much higher than in Japan and the EU. (Yes, here in the home of "free market capitalism" we pay about double what other developed country citizens pay for these services.)

As profits plummet, major companies exit or take over marginal competitors and then try to muscle into whatever profitable business remain. You get what we have now: Everybody everywhere is pursuing the same goal: creating another Silicon Valley of innovation and wealth generation.

So everybody everywhere is building business parks and examining their education programs, lining up tax breaks for biotech, nano-engineering, software, etc.-- the "clean" wealth-producing industries of the future. Hmm, do you foresee future overcapacity in the making? How many "miracle drugs" will produce billion-dollar profits when dozens or hundreds of research centers start producing competing medications? Now that Intel, Appied Materials, et al. and their Japanese, Chinese, European and Korean silicon-etching rivals are all jumping into silicon-based solar panels, how can anyone corner billion-dollar profits? The productive capacity of the major economies is so vast they can quickly outstrip even robust demand.

Flat-screen TVs were supposed to be the profit-center for consumer electronics giants, but that hope has fizzled as everybody and their brother jumped in and built factories with stupendous capacity. Ditto for steel, autos, you name it: China's capacity to produce steel and autos has already grown far beyond potential demand, and the shakeout is already visible.

Whatever profit centers remain are either protected by enormous entry costs (commercial aircraft, silicon wafers, etc.) or by ephemeral marketing legerdemain and temporary technological advantages (iPod, iPhone, Blackberry, etc.)

Even as the forces of competition and overcapacity relentlessly squeeze profit margins, the costs of raw materials and energy are rising. While it's comforting to hope prices for materials will plummet in a global recession--and no doubt they will temporarily--The Great Price Wave is fundamentally based on demographics.

As populations surged and wealth increased in the 13th and 16th centuries, demand eventually outstripped supply. Now that a billion additional people have gained some access to developed-nation type consumer lifestyles, even global recession will be unable to repeal long-cycle rises in commodity and energy prices.

You cannot double the number of global consumers and have no effect on price.

Two other factors feed overcapacity: an oversupply of labor in developing countries and robotics in developed economies. As competition and rising input costs squeeze profits, manufacturers turn to automated production or cheaper labor markets. Even now some manufacturers are fleeing "rising labor cost" coastal China for lower-labor cost climes in the interior, or elsewhere in Asia. Frquent contributor Albert T. just sent in this link: China Manufacturing Shrinks for First Time on Record.

Some auto plants in Japan are so automated that the entire plant only requires about 125 workers. That's how you get global overcapacity in virtually every manufactured good.

2. As manufactured goods remain low in price, the cost of capital rises. The seeds of such a rise in the cost of capital are already clear: with credit contracting and stupendous capital impairment/losses being taken, there will be much less capital and borrowing power sloshing around the global economy. As a result, those who want access to capital (borrowing actual cash saved by someone somewhere) will be bidding against others for that dwindling capital.

Yes, the sovereign wealth funds of oil-exporters are currently groaning under the weight of oil profits, but three long-term trends will eat away at the surplus capital available to oil-consuming nations like the U.S.:

A. oil-exporters' skyrocketing populations

B. oil-exporters' skyrocketing consumption of their own oil

C. the eventual demand of oil-exporters' populace for greater domestic investment

3. Income disparity increases as owners of capital reap increasing gains. Fischer showed that even as purchasing power of most citizens declined, the cost of rents/food/energy rose. Strangely enough--or perhaps not so strangely-- we see just these trends developing in the present. Demographics--that additional billion consumers--is driving up the cost of food and energy, and the decline in purchasing power is motivating people to move from marginal exurbs and suburbs to cities with nearby FEW resources (food, energy, water), enabling landlords in desirable areas to raise rents.

Perniciously, the rising cost/dearth of capital makes it harder for wage-earners to join the rentier class, i.e. buy buildings and dwellings in these desirable areas.

We cannot know precisely how these long-term cycles will interact and play out, but we can know this: those who understand them will have a much higher probability of weathering the future/prospering than those who have no idea of the forces at work beneath the surface of everyday life.

(I discuss the impact of these trends in my soon-to-be-published book, Weblogs & New Media: Crisis in Marketing.)

Excellent New Readers Journal Essay:

Read all five of this month's superb essays if you missed them

Why the Trend in Oil Is Up (José de Freitas, July 30, 2008)

Although I'd be lying if I said I am certain of which direction the oil price is going, my gut feeling is telling me that it's going up as a general trend, despite brief respites. A few points have not been sufficiently made, and I think Rainer H.'s piece exhibits some of the problems those points would address.

Thank you, Ben G. ($50), for your second wonderfully generous donation this year and for your ongoing contributions of ideas and encouragement to this site. (Les Pauls rock!) I am greatly honored by your support and readership.