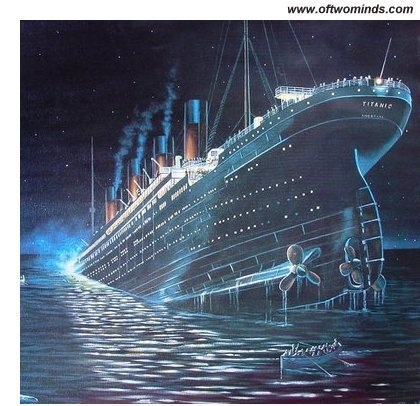

We are like passengers on the Titanic ten minutes after its fatal encounter with the iceberg: the idea that the ship will sink is beyond belief.

As we all know, the "unsinkable" Titanic suffered a glancing collision with an iceberg on the night of April 14, 1912. Ten minutes after the iceberg had opened six of the ship's 16 watertight compartments, it was not at all apparent that the mighty vessel had been fatally wounded, as there was no evidence of damage topside. Indeed, some eyewitnesses reported that passengers playfully scattered the ice left on the foredeck by the encounter.

But some rudimentary calculations soon revealed the truth to the officers: the ship was designed to survive four watertight compartments being compromised, and could likely stay afloat if five were opened to the sea, but not if six compartments were flooded. Water would inevitably spill over into adjacent compartments in a domino-like fashion until the ship sank.

We can sympathize with the disbelief of the officers, and with their confused reaction, simultaneously reassuring passengers and attempting to goad them into the lifeboats. With the interior still warm and bright with lights, it seemed far more dangerous to clamber into an open lifeboat and drift off into the cold Atlantic than it did to stay onboard.

As a result, the first lifeboats left the ship only partially full. Only when it became undeniable that the ship was doomed did people attempt to "make other arangements," but by then it was too late.

The tragedy was a cruel mix of human error (entering an ice field at nearly top speed, 23-25 knots), hubris-soaked planning (only enough lifeboats for half the passengers and crew) and design flaws: the high-sulfur iron hull plating did not bend when struck by the ice, it shattered like china.

As noted above, the watertight compartment design was also flawed; indeed, some studies have found that the ship would have stayed afloat an additional six hours had there been no watertight compartments, as water would have sloshed evenly along the entire length of the vessel.

I think this perfectly describes the present. Our financial system seems "unsinkable," yet the reliance on debt and financialization has already doomed it, whether we are willing to believe it or not.

Maybe the illusion that the ship is unsinkable can be maintained for another year or two; the Status Quo's success in masking the ultimate fate of the financial system for the past four years supports the belief that there is literally no limit to the Federal Reserve and Treasury's power to keep the ship afloat, regardless of the cost. In other words, the Fed and Treasury are perceived as "unsinkable."

That illusion has cost trillions of dollars, trillions of dollars of new debt that now burden the taxpayers: $2 trillion added to the Fed balance sheet, $1.2 trillion in secret giveaways to the banking cartel, and $6 trillion in additional Federal debt/spending.

Yet few of us are willing to entertain an exit from the belief system that supports the Status Quo. We are like passengers on the Titanic ten minutes after its fatal encounter with the iceberg: we can't believe this grand ship could sink, so we do nothing while it is still possible to influence our fate.

We could insist on changes to these doomed policies, but we do not; why?

Some of our reluctance can be attributed to disbelief, as the gap between what we know is inevitable--the ship will sink beneath the waves--and what we currently see--a proud, mighty ship, apparently only lightly damaged--is so wide.

But if we delve deeper, we discern how calculations of risk and gain yield faulty assessments of self-interest. While the ship appears structurally sound, it seems risky to clamber into an open lifeboat and drift away into the freezing night, while the supposed gain (saving our life) is questionable: from the warm deck of the ship, it seems that climbing into a small lifeboat would place our life far more at risk than staying on board the mighty ship.

This assessment of self-interest was tragically flawed, and by the time the impossible (sinking) had become the inevitable, it was too late to change the fate we’d selected back when all seemed permanent and secure.

The point of this exercise is to reveal just how illusory our assessment of self-interest and security can be, and how prone we are to making decisions based on the present even when our rational minds are well aware that it is unsustainable.

The financial system of the United States of America is like the Titanic. Hubris led many to declare it financially unsinkable even as its fundamental design was riddled with fatal flaws and the human pilots in charge ran it straight into the ice field at top speed.

We have some time left before the ultimate fate is visible to all. Ten minutes after the collision, the Titanic's passengers had 2 hours and 30 minutes before the "unsinkable" ship sank. How much time we have left is unknown, but the bow of the ship will be visibly settling into the icy water within a year or two--and perhaps much sooner.

We cannot know when the Central State and financial system will destabilize, we only know they will destabilize. We cannot know which of the State’s fast-rising debts and obligations will be renounced or written down; we only know the debts and obligations will be renounced in one fashion or another.

The process of the unsustainable collapsing under its own weight and being replaced with a new, more sustainable model is called revolution, and it combines cultural, technological, financial and political elements in a dynamic flux. Though these systemic transitions can be profitably understood as cycles, history only illuminates past transitions; what the new arrangement will be is our choice.

| Thank you, Christopher T. ($100), for your outrageously generous contribution to this site--I am greatly honored by your support and readership. | | Thank you, John D. ($20), for your much-appreciated generous contribution to this site--I am greatly honored by your support and readership. |