Solutions Part Four: Self-Reliance

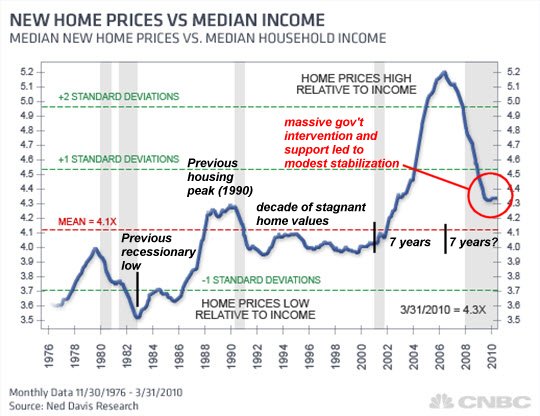

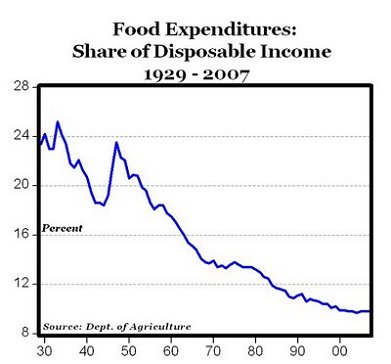

As essayist/farmer Eric Andrews notes, it makes little financial sense to grow one's own sustenance now due to the all-time lows in the cost of food. We might also conclude that it makes no sense to change the oil in your own vehicle, refinish furniture (new crappy particle board furniture from China is "cheaper" than refinishing) or indeed, to do anything for yourself: it can be outsourced or performed by a global corporation "cheaper" than you can do it.

This may partially explain why Americans have generally lost the skills and curiosity needed to do anything real for themselves, such as cook/bake, effect household repairs, write their own code, or build a business or house from scratch.

As noted earlier this week, the other factor is dependence on the Central State, which enervates those who have sacrificed autonomy and political independence by depending on the State--a condition closely related to addiction.

Self-reliance receives abundant lip-service but few seem to have any interest in pursuing it in the real world. How many hours are spent in households watching TV, checking Facebook and Twitter, IMing on cellphones, playing with iPods, email, websurfing, etc., and how many are spent learning or doing anything of value in the real world?

The answer to that question defines America's level of self-reliance: poor to zero.

So if there are few if any financial incentives to self-reliance, why should we bother learning to do things for ourselves? In a soulless culture, then the answer is "obvious": there is no reason, so passive, resentfully entitled complicity with the status quo is the "solution."

But if a soul flickers even partially alive in a human being, they will desire autonomy and independence, and the joys of curiosity, learning, failure (yes, failure, for it is the Great Teacher) and mastery will arise to fill the vacant darkness at the center of the American Empire and "lifestyle."

Here are Eric's recent essays:

Sleep, Dreaming, and National Suicide (June 26, 2010)

True Confessions (on Liberty and the Republic) (August 14, 2010)

MY INTRODUCTION: "If I set out to encapsulate my Survival+ critique in a mere 2,700 words, I could do no better than this: a closely reasoned case for opting out, small-scale, resilient solutions and radical self-reliance--the very heart of the Survival+critique.

Some readers seem to think that this is an implicit recommendation for living in mud huts and a return to a pre-technology Dark Ages. Nothing could be further from the future I envision, which is radically better, more sustainable and more humane than the present dominated by an insatiable Savior State and its Global Empire which protects and empowers a handful of cartels and fiefdoms at the expense of the world and the U.S. citizenry."

Solutions Start at Home

by Eric Andrews

In my last article I pointed out that the real problem with writing about solutions is that no one can know what you need or tell you what to do. Your situation, your needs are different than my needs and situation, so only you know what is best. That’s Liberty: you are completely in charge but completely responsible when things go good or bad. And isn’t that the way it should be?

But still, solutions are of the essence. So although I can’t tell you what you should do at your house, I can tell you what we do at mine. Hearing things—how solutions of any kind are assembled—can give us ideas for what we all can do.

In this new era, all solutions will be local. Local weather, local availability, local conditions will dictate what will and won’t work. I live in the Northeast, out on the Lake Plains east of Buffalo, NY—a land of small woodlots and small fields. It's rainy and cold both spring and fall, with sustained snows of 2-3 feet average, 6 feet at a single storm is no surprise, yet also windswept and baking for much of the summer. Things that work for me may not work for the deserts of California or the Southwest, the vastness of Canada, or the moderate Carolinas. But then again, who can say what can or can’t be done?

Apple Lawn is a small farm of 52 acres, which hasn’t been commercially worked in a generation, as the price of food has been too low all that time. I know that may seem impossible, but the price of food has never been this low in human history.

But although food is cheap and I have a job in the city, the farm still calls with rich clay soils and the endless optimism of spring.

Having worked the same quarter acre garden for decades, providing us with year’s supply of tomatoes, sweet corn, green beans, eggplants, peppers, lettuce, asparagus, and whatever strikes our fancy, last year we opened up a second quarter acre plot on soil fallow for more than a decade.

It’s been said that the end of oil will be the end of us all as tractors, fertilizer, and pesticides, will become unavailable at any reasonable price. This is misguided perception by people who didn’t further their research into how farms and gardens work. It may be true that you can’t intensively-garden 52 clay acres without 52 well-trained farm hands; however, a modest trip back in time—merely to the 1940’s—shows how it was done by my own grandfather, driving his team Molly and Dolly through the clays of slow-moving Niagara county. It's true you can’t grow corn year-on-year on the same soils, for it will degrade and wash away into a ruinous hardpan or dustbowl. However, you don’t have to--you simply use the crop rotation that’s been industry standard since the early Middle Ages. You divide your large fields by four and one of them lies fallow each year, renewing the soil. This would be seeded to hay—a weed of your choosing—and fed to the animals who would then fertilize the other three fields.

This is why small farms of the past thousand years included animals, and why before the brief era of cheap oil, pesticides and fertilizers, this diversified, small-farm plan prospered over other methods, nor would an animal-free farming necessarily be recommended. Should the price of oil rise, the clock will rewind as far as it has to, back to the point where oil input meets availability or pasture is replaced by biodiesel. This isn’t terribly hard, but it takes an uncomfortable period of time to retool. Reserving one quarter of your land to pasture nearby animals is an indispensable piece of this. No more agri-business, no more factory farms, and the smaller it becomes, the happier the cows, chickens and other stock, living in the sunlight and unplowed grass they were born to. That makes happy people.

In our county, some changes are already happening: with the price of chemical applicants rising so rapidly, farmers quickly adopted new old methods. Instead of plowing before planting, the farmers here have planted soybeans (a renewing crop) right over existing cornstalks, and under-seeded winter wheat to hay (another renewing crop), thus saving both the diesel plowing costs and the fertilizer costs. Others have gone one better and planted beans following cabbage, wheat following cabbage, or other crop combinations in series, pulling out two crops in a single year. Gains of this sort are scarcely touched upon so long as food is too cheap to grow and harvest, but the answers are out there, waiting for immediate deployment to a hungry world.

Being 10 years fallow, our field needs nothing. Why did we expand to it? No reason at all. I tell you in all honesty, you’re not going to save much growing food compared to buying staples like corn, beans, rice, and hardly anything for your vegetables—and certainly not the storage staples like carrots or winter cabbage. Your food costs really exist only in processed foods: soda, diet microwave dinners, breakfast cereals. We grow food simply because we like to see it grow. I have no words for this, but somehow it’s improper to buy foods made by faceless men 1,000 miles away and leave our backyard untouched. No responsibility. No contact. No reality. No life. No happiness.

So, we plowed it to plant the bulk crops that would have consumed the old garden: our three Seneca sisters: field corn, dry beans, and pumpkins. I know some will be saying, “that’s all well for you rich folks with a 40-year old tractor, but what about the rest of us?” It’s really a small matter: a quarter acre is actually a nuisance to break with a plow and disc, barely room to turn around; besides, I could hire it done for 30 years for the price of a tractor. I could prepare it with a collar and carriage horse, a yoke and a milk cow, or maybe two donkeys, and in fact the equipment to do so remains strategically located in flower beds around our neighborhood. --Or you could do as Thoreau and turn it over in a few evenings with a shovel and a pair of heavy shoes. It only needs to be done once, so your investment will be divided by however many decades it’s in use. Once turned or broken, you can rent a rototiller for a very small sum and finish the seedbeds in two hours once a year, and will be all it requires for every season thereafter.

So we plowed. We planted. When? Why, in the spring, of course! I say that not to be flippant, but in Western NY any time it’s not frosting and dry enough to work is the right time, right up to high summer. We planted this year in mid-May, but have often planted the same garden on the 4th of July with little difference. That’s just where we live with the world’s largest freshwater lakes cooling us. That’s how simple growing is.

Here’s the secret garden books don’t tell you: plants want to grow. A lot. They’re saving their lives, just as you would, dropped from the sky to some small piece of ground somewhere in the world. They do all the work, stretching and growing in the sun. What do we do in comparison? Am I somehow instrumental in pulling them out of the ground? No. Do I bottle-feed or tuck them in at night? Not a bit. All I do is tip conditions in their favor and insure they remain that way, so that one plant grows and not another. So beans and not, say, the amaranth that grows so vigorously here. Not that the amaranth is my enemy—I eat that too—but I happen to be looking for beans in this particular patch. The amaranth is welcome to grow anywhere else it finds.

To insure the beans keep their unfair advantage, I weed them a couple times ahead of their faster-growing competition. Weeding? Aaaaaiii! This is the part where people lose interest and call shenanigans on all this hard work. But I don't work, I cheat. And why shouldn't I? Over 100 years ago, a device was invented called the "Planet Jr. wheel hoe" which any thinking man must consider to be the greatest invention of the century. I encourage any one who row-gardens to run, not walk, to get one. They lasted so long and required so little that the original Planet Jr. company went out of business in 1968. It took over 40 years, but finally enough have broken or rusted away that they are being re-cast again, on ebay.com or at Planet Jr.(no affiliation or experience with vendor).

If that’s too expensive, buy one from an antique dealer or out of someone’s front yard. They should go cheap: other than kitschy decoration, nobody remembers what they’re for anyway.

To weed with one of these marvels, simply walk up and down between the rows every five days, like pushing the sweep blades like a grocery broom. You see, weeds germinate but remain tiny and fragile for a week before becoming visible. If you disturb them even slightly in that time, they will wither before you ever see the smallest sprout. Voila: no weeds and rows as clean as wall-to-wall carpet. All you need to do is walk the rows once a week. Or if you’re lazy, do a few rows until you’re tired of it, and the next day walk a few more, and so on back to the beginning.

It has no motor, requires no upkeep, and can stay outdoors indefinitely. When the handles finally rot off in 20 years, they can be replaced. The iron parts could even be cast in your backyard with the right setup: backyardmetalcasting.com. For the purpose, this investment will beat any tractor made. For the secret is in the knowledge not the tools. Five days is that secret.

Contrary to national (or NY City) belief, New York is an large and predominantly rural state as well as an agricultural powerhouse. Here in the Lake Plains we have more in common with Ohio or Iowa than with small and moderate New England—90º in summer is given, and although the lows are limited to 0º by the Great Ontario (809 feet deep!) our total snowfall averages 8 feet. By the time it’s 90º in the summer, the cool morning is too short to weed in, so I don’t.

Sure, I could have a show garden, perfect and weed free, but only by climbing up the law of diminishing returns. For here’s the second secret to gardening: plants like to grow together. In nature, you never find a single plant growing alone in bare soil—bare soil is an anathema to Nature. Plants forever grow together—either their own species or some other—and in my experience they languish when laid out in isolation.

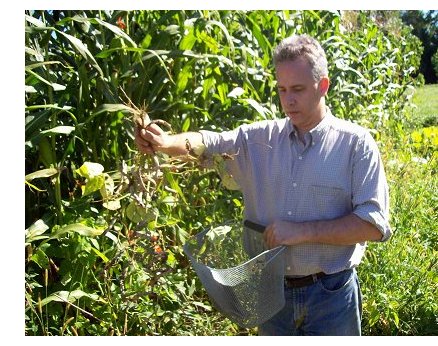

You notice from the picture that the weeds have long outgrown my bean rows. Yes, those are rows. Yet the diminished yield from permitting weeds is negligible compared to the benefits these volunteers provide: microshelter from stripping winds, deep fertility of soil, moderate shade conserving water in drought, and habitat for a wide variety of insects and other creatures who insure that no one species of bean-eating creature can get out of control. This saves me work all around, and is well-known, both to the original natives and in challenging locations like the Amazon, where weeds must grow with the fields or the settler’s garden would be wiped out. (for more information see Weeds: Guardians of the Soil by Joseph A. Cocannouer.)

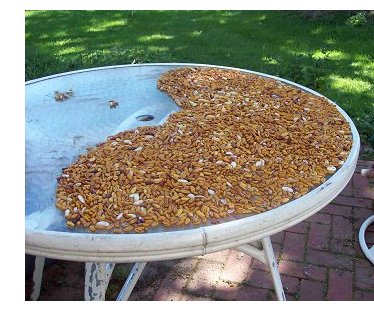

But today it’s the harvest. Frost is now 30-60 days away and nothing flowering will mature in the time left. To tip the balance in my favor again, I pull up the weeds and throw them aside so their remaining seeds cannot overwhelm the space. This is made easy by the damp shade and deep soils they created for their roots. At the same time, I pull the beans I find and strip them into a bicycle basket and dump them on the patio table, although any blanket or tarp would do. Then I scatter buckwheat on the open ground to hold the soil through winter, a “weed” of my choosing. Soil should never be left bare if it can be helped, and if approached intelligently, there is never a need.

Traditionally, beans were put on the tin roof to dry. Over the tin, if you’re in the dry south, or under, if you’re in the rainy, dewy north. Before tin was available, the pods were threaded on a string and hung on the cabin wall. Then you’d pull out a basket when your friends were over and shell them on the porch. You weren’t doing anything while talking anyway, and it was fun and satisfying. However, as I have to go to work on Monday, I get impatient and we shuck them in the afternoon sun and throw them in the dehydrator. They must be fully dry or they will mold in the jars, yet they mustn’t overheat or it will kill the seed. In the past, a shelf by your wood stove would have served the same purpose. This beautiful variety is called Tigereye, from Seeds of Change. Strangely tropical, this (replantable) purebred flourishes here in wet summer heat while soldier beans and other New England varieties languish. I planted perhaps a cup. As you can see, it returned over 2 gallons. This is what you’d call “tangible return-on-investment,” a positive “Energy-in, Energy-out” ratio of 32:1. This is how you know it is worthwhile, although it does not account my time. But what was I going to do otherwise? Read more about financial fraud and destruction? What good would that do? With my food, my life, under my own control, it's no longer as important to me whether markets freeze up or not.

This is all of the non-cannelloni/non-black beans we need for the year, and what was my investment? $2 for the seeds, $2 for the field, taking in $6 worth of beans—but I already said food is so close to free as not to matter. What we get a variety of bean that’s unavailable, wonderfully beautiful, which has a flavor unmatched, for merely the use of my free time. Square feet? About 120', the size of a one-car garage.

Less tangibly, our food system is quite long and increasingly fragile. What growing provides in these troubled times is that intangible called “resilience”. It gets me off the single-provider plan—one income and one supplier, and puts my life more under my long-term control. That costs and like other insurance, the accrued benefits aren't visible while you're making the payments. For simple as growing food is, to grow in quantities necessary to live on you need the field already broken, the seeds already at hand, and several year's experience under your belt. During the flood is not when you want to buy a rowboat. Landfall of the first hurricane is not when you want to buy plywood. These things may never happen, but history says that eventually they will. Our nation is no exception.

Should the knowledge of these things die, as they are dying now, they cannot easily be recovered, living as it does in the minds of ten-thousand aging men and women, each knowing only what works for them, in their own area. Neither can any book tell you how things must be done on your property, in the desert, in the mountains, at the bottom of the hill, by the lake, in the sand, in the clay, in the snow. Nor can I advise any other, as conditions a mile from here are different than mine. Knowledge, being the cheapest to acquire, is also the most expensive—it will cost all the years of your life.

"Experience is a dear teacher, but fools will learn in no other." --Benjamin Franklin

Gardening is not assembly-line work. You can’t read a book and assemble your product by the numbers. Or rather I should say that NO skill is able to be picked up without experience: that’s the difference between information and knowledge. The internet provides a fire hose of unfiltered information. But without long watching, long practice, and personal experience of how to apply it, that knowledge remains as useless as a box of bolts, useful only if applied by the skill and imagination of the workman whose intelligence knows what to add and what to take away.

You expect to read a book on smithing and make yourself a sword? Leave that to the movies. Reality is more like a guitar: easy to play badly, but taking a lifetime of experience to master.

So this is what’s doing at Apple Lawn Farms this week.

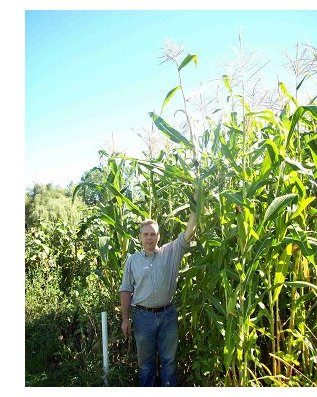

If you look behind me, you’ll see a colonial variety of “Bloody Butcher” field corn. Another purebred, non-hybrid with viable seeds, it’s wildly abundant, proven over generations of harsh conditions, and growing over 12’--so high you literally cannot harvest the ears without a ladder. So why are we growing terminator seeds, or specialized hybrid seeds which are equally unviable? Well, because it’s easy and we can. But within a few years I could grow enough seeds to plant the township with purebreds.

We can do these things. As food comes off its all-time, rock-bottom lows, I rather expect we WILL do these things. And what’s more, YOU can do these things. In your backyard, with the minimal effort and expense. Grow them for the happiness of watching things grow, making a rich and beautiful life at your house, a thing money can’t buy.

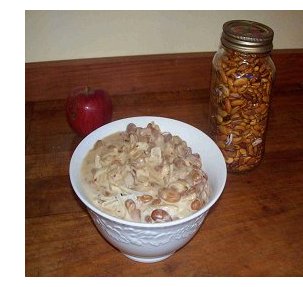

And the payoff, a world of fresh eats:

Requirements for this project:

120 s

quare feet

Borrowed shovel

Borrowed seeds

Wheel hoe

Shopping bag

Patio table

Louisa's Vegetarian Baked Beans:

* 2 1/2 cups dried beans, soaked 5 hours

* 1/3 cup molasses

* 1/4 cup brown sugar

* 1 1/2 Tbsp dry mustard

* 1/4 teaspoon powdered cayenne

* 1 tsp smoked paprika (or a drop of liquid smoke)

* 2 teaspoons soy sauce

* 2 medium onions, chopped into large pieces

* 2 bay leaves

* 3 cloves garlic, minced

* 1 large tomato, chopped

* 1 teaspoon salt

* olive oil or butter

Drain the soaked beans and place in a large pot with water to cover. Simmer over medium heat for two hours or until soft, adding water if it's needed. Drain any remaining water.

Saute the onions in butter or olive oil until they soften. Mix with the rest of the ingredients and then the beans. Pour into an appropriately sized ovenproof dish and cover, either with a lid or tinfoil. Bake in a 350 degree oven for an hour, give or take 15 minutes or so. It's not a picky dish.

The beans can also sit in the fridge for a day or so, after being mixed together but before being baked. They're really very agreeable.

They make a great meal with cornbread and any green vegetable.

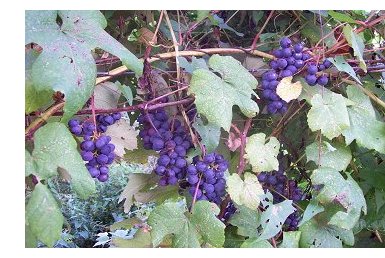

Extra Credit:

For the ultimate in low-work eating, try grapes:

For $12 a vine you can have a gallon of fruit a every year for 100 years.

I am doing my best to respond to correspondence but am unable to keep current.

If you would like to post a comment where others can read it, please go to DailyJava.net, (registering only takes a moment), select Of Two Minds-Charles Smith, and then go to The daily topic. To see other readers recent comments, go to New Posts.

Order Survival+: Structuring Prosperity for Yourself and the Nation and/or Survival+ The Primer from your local bookseller or from amazon.com or in ebook and Kindle formats.A 20% discount is available from the publisher.

Of Two Minds is now available via Kindle: Of Two Minds blog-Kindle

Thank you, Raimund D. ($100), for your astoundingly generous contribution to this site-- I am honored by your support and readership.