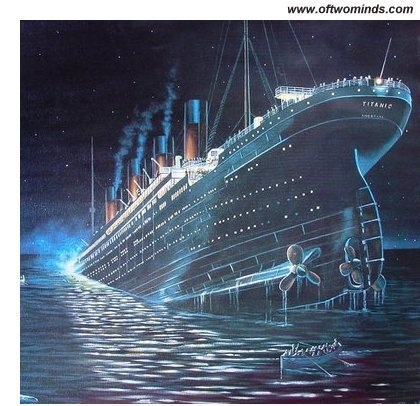

Dow 30,000 is "unsinkable," just like the Titanic.

A recent Barrons cover celebrating the euphoric inevitability of Dow 30,000 captured the mainstream zeitgeist perfectly: Corporate America is firing on all cylinders, the Federal Reserve's god-like powers will push stocks higher regardless of any other reality, blah blah blah.

While the financial media looked elsewhere for its amusement, the coronavirus epidemic in China just poured fentanyl in the Dow 30,000 punchbowl. The mainstream continues to guzzle down the punch, oblivious to the fentanyl, confident that the coronavirus will quickly fade and China will soon return to its winning role of growth chariot pulling the global economy to ever greater heights.

The media's focus is solely on the first-order consequences: the number of infected people and fatalities, government responses such as quarantines, and so on. The general expectation is these first-order consequences will dissipate shortly and life will return to its pre-epidemic status with virtually no significant changes.

If we consider second-order effects carefully, we draw a much different conclusion: China will experience social unrest and economic dislocation that will unleash self-reinforcing chaos in global markets. This is not a mainstream opinion, of course, because the mainstream assumes second-order effects simply won't matter, i.e. they don't exist. As I describe in my latest book,

Will You Be Richer or Poorer?, acting as if inconvenient realities don't exist doesn't make them actually vanish. Ignoring realities that are difficult to measure or that don't fit the

happy story is ultimately suicidal.

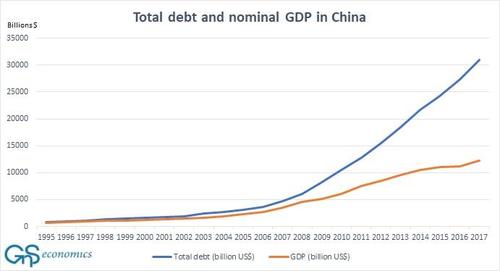

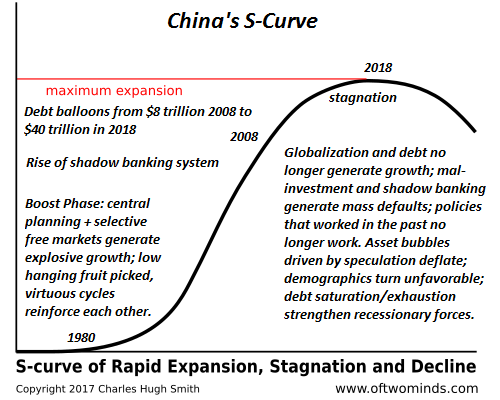

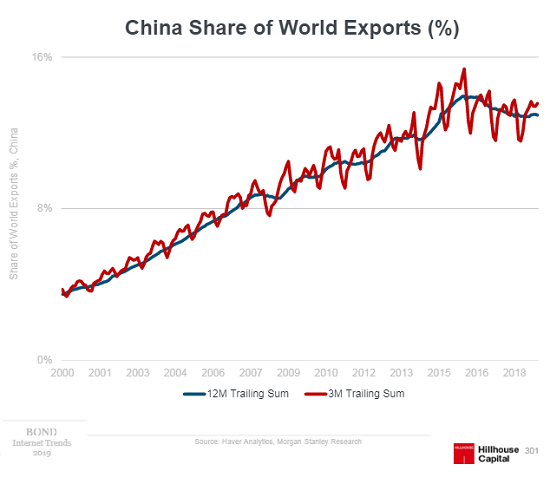

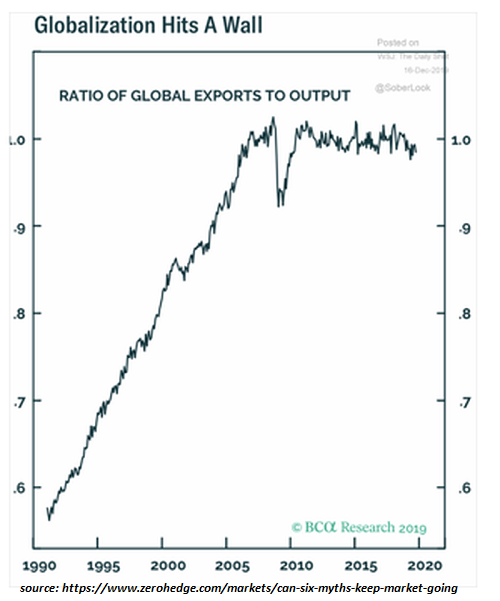

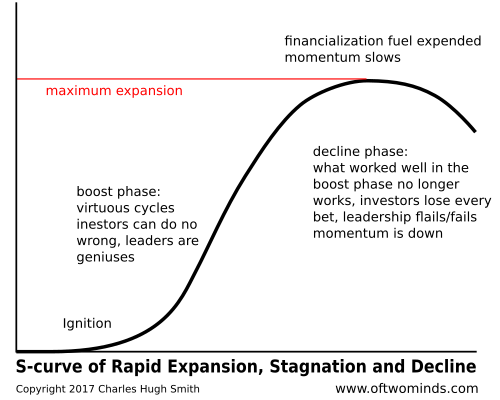

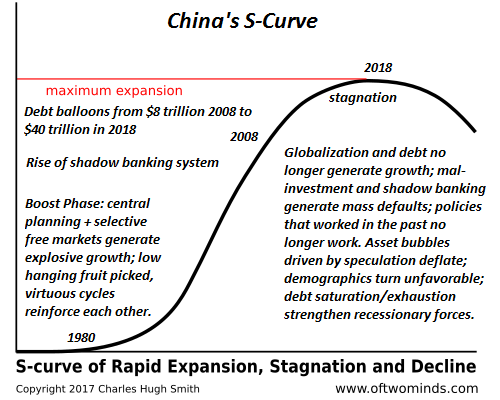

Though China Bulls will never admit it, China's economy has become increasingly fragile in a process of diminishing returns reflected in the chart of China's S-Curve below. What worked in the boost phase (picking the low-hanging fruit of development) no longer works.

The conventional view in the West is that the Chinese people are docile and obedient, obeying the central government's edicts without question. The idea that the working class in China could refuse to comply is not even on the margins of Western understanding.

But if we consider the thousands of spontaneous protests and wildcat strikes against authority that have occurred in China in recent years, we realise it's Americans who are docile and obedient, slavishly worshiping at the altar of the Federal Reserve / Dow 30,000 while their "billionaire betters" pile up fortunes and political influence, reducing the vaunted American middle-class to passive, beaten debt-serfs and tax donkeys.

Despite the paper-thin veneer of official Communist rhetoric, the social contract in China is entirely financial: you (the ruling elites) make us more prosperous every month and we'll obey. Prosperity is of course financial--higher wages, more social benefits, higher real estate valuations, and so on-- but it also includes intangible forms of capital such as greater security, cleaner air and water, wider avenues of social mobility, etc.

The official mishandling of the coronavirus epidemic from the top down tells the Chinese people the unfortunate reality: you don't count, you don't matter. All that matters is the leadership saving face, and if millions of working-class Chinese people are sacrificed or needlessly put in harm's way to save the leadership's face, then the masses should quietly accept their completely needless losses and suffering.

This is a complete abrogation of the implicit social contract China's people have come to expect of their leadership. The masses have accepted systemic corruption that enriches the few (Party leaders and crony developers, etc.) at the expense of the many because the many were gaining greater prosperity and security. But that advance has stalled in recent years as the costs of essentials have soared and wages haven't kept pace.

The favored elites have of course kept pace, and since they control the media and machinery of governance, the unhappy slippage has been successfully buried beneath bogus official statistics and relentless suppression of any leakage or dissent.

(Note that doctors who attempted to go public with their fears of the coronavirus in early January were reportedly arrested to shut them up--par for the course for anyone who doesn't comply with face-saving official prevarication.)

But being exposed to a potentially fatal virus because it pleased the leadership to suppress the facts will trigger second-order effects that will not dissipate. The same can be said of economic and financial second-order effects that will disrupt supply chains and China's precariously over-leveraged shadow banking system.

Those expecting the Chinese workers to be cowed by 100,000 security cameras will be surprised when workers tear down every single camera and the police and People's Liberation Army soldiers decline to kill their fellow citizens.

Nobody expects China's social order or economy to unravel as a second-order effect of the epidemic, and that in itself is a sound reason to not dismiss the possibility too readily. Second-order effects: consequences have their own consequences.

Meanwhile, back on the Corporate America Ranch, Second-order effects may upset all the happy-story assumptions of Chinese suppliers magically being unaffected and workers whose jobs have vanished accepting their downward mobility without complaint.

U.S. companies may find their products are not available in the expected quantities and at the expected prices. Since 90% of American wage-earners have stagnant incomes, Corporate America has no pricing power, i.e. ability to raise prices and make them stick, so profits will be slashed as sales stagnate along with wages.

The hubris-soaked fantasy that the Fed will jack up stock valuations forever regardless of sales and profits will run aground on the unforgiving shoals of reality and all the hidden fragilities in America's economy will emerge: too much leverage, too many zombie companies kept alive by debt, too much debt and not enough collateral, too many small businesses one tiny tipping-point away from closing for good and laying off all employees--the list is nearly endless.

Once all the second-order effects have erupted and triggered their own chaotic consequences, we'll look back at the complacent euphoria that America is both dependent on Chinese labor and production yet magnificently detached from any consequences of China's downward spiral and marvel at the herd's self-congratulatory hubris, willful blindness and unforgivable negligence.

Down this slippery path lies Dow 10,000. Dow 30,000 is "unsinkable," just like the Titanic.

My recent books:

My recent books:

NOTE: Contributions/subscriptions are acknowledged in the order received. Your name and email remain confidential and will not be given to any other individual, company or agency.

Thank you, Robert M. ($5/month), for your superbly generous pledge to this site -- I am greatly honored by your support and readership.

| |

Thank you, Rob S. ($5/month), for your splendidly generous subscription to this site -- I am greatly honored by your support and readership.

|

Read more...