Everyone expecting a quick resolution to the epidemic and a rapid return to pre-epidemic conditions would be well-served by looking beyond first-order effects.

While the media naturally focuses on the immediate effects of the coronavirus epidemic, the possible second-order effects receive little attention: first order, every action has a consequence. Second order, every consequence has its own consequence.

So the media's focus is the first-order consequences: the number of infected people and fatalities, government responses such as quarantines, and so on. The general expectation is these first-order consequences will dissipate shortly and life will return to its pre-epidemic status with virtually no significant changes.

Second-order effects caution: not so fast. Second-order consequences may play out for months or even years even if the epidemic ends as quickly as the consensus expects.

The under-appreciated dynamic here is the tipping point, the imprecise point at which a decision to make fundamental changes tips from "maybe" to "yes."

These tipping points are often influenced by exhaustion or frustration. Take a small business that's been hit with tax increases, additional fees, more regulatory compliance requirements, etc. When the next fee increase arrives, the onlooker might declare that the sum is relatively modest and the business owner can afford to pay it, but the onlooker is only considering first-order effects: the size of the fee and and the owner's ability to pay it.

To the surprise of the onlooker focusing only on first-order effects, the second-order effect is the owner closes the business and moves away. Invisible to everyone focusing solely on first-order effects, the owner's sense of powerlessness and weakening resolve to continue despite soaring costs and declining profits has slowly been moving up to a tipping point.

Beneath the surface, every new fee, every tax increase and every new regulation has pushed the owner closer to "I've had it, I'm out."

When the owner shuts the business, onlookers can't understand how one little extra fee could trigger such a fundamental change. The observer is only looking at the new fee as a single cause with a single consequence. In the real world, each new fee, tax increase and regulation was another link in a causal chain of consequences generating consequences.

Turning to the possible second-order effects of the epidemic in China, let's start with the decision to keep supply chains in China. The reasons to keep supply chains in China have been dwindling for years: wages and other costs have been rising, the central government has increased demands for technology sharing, the general sense that foreigners and foreign companies are no longer needed or wanted, and the trade war, which is more or less in a truce phase rather than over.

One common belief is that it's "impossible" to move supply chains out of China. This is a classic first-order effect analysis. When the supply chain gets disrupted for one reason or another and alternatives must be found, alternatives are found. What becomes "impossible" isn't moving the supply chain from China but keeping it in China.

The mistake made by those only considering first-order effects is that a modest effect "should" only generate modest consequences. For the observer focused solely on first-order effects, if the coronavirus epidemic blows over as expected, then supply chains "should" be unaffected because the effect is quantitatively modest.

But once we start considering cumulative second-order effects and potential tipping points, then the disruption of supply chains caused by the epidemic, no matter how modest, could be "the last straw" to those who had beneath the surface already shifted from "never leave China" to "maybe leave China." The epidemic could tip the decision process into "must leave China."

Consider two executives, one who looked at the longer term consequences of being dependent on production in China and began establishing alternative suppliers at the start of the trade war 18 months ago, and another exec who looked at the first-order hassles and expenses of moving out of China and stayed put to minimize short-term expenses.

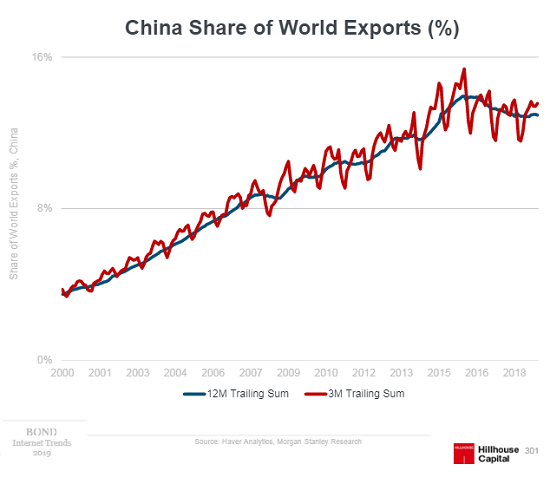

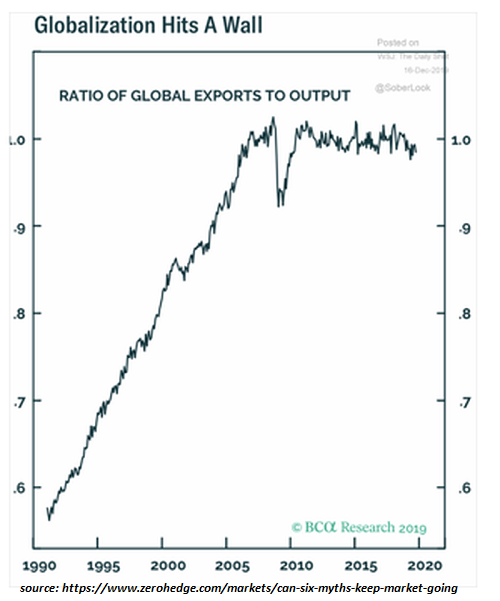

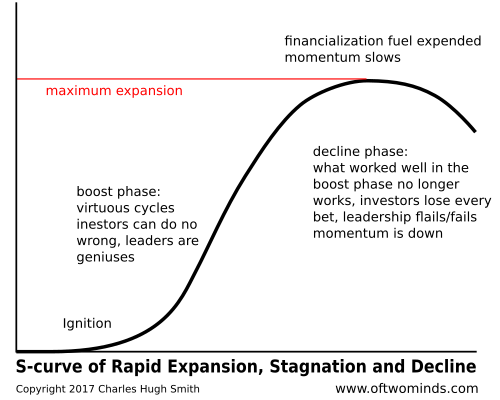

Individual decisions add up to trend changes, and these charts reflect a trend change in globalization and China's share of global exports. Globalization and China's share of global exports have both plateaued and are now entering the stagnation / decline phase of the S-Curve.

Everyone expecting a quick resolution to the epidemic and a rapid return to pre-epidemic conditions would be well-served by looking beyond first-order effects and easy assumptions that the consequences of the epidemic will be near-zero.

Here are some informative science-based links on the coronavirus, courtesy of longtime correspondent Cheryl A.:

NOTE: Contributions/subscriptions are acknowledged in the order received. Your name and email remain confidential and will not be given to any other individual, company or agency.

Thank you, John D. ($50), for your magnificently generous contribution to this site -- I am greatly honored by your steadfast support and readership.

| |

Thank you, Robert S. ($50), for your superlatively generous subscription to this site -- I am greatly honored by your steadfast support and readership.

|