The end of debt-based affluence: welcome to The Last Christmas in America (TLCIA).

Almost 35 years ago, as unemployment rose toward 10%, the January 1975 cover of Ramparts magazine blared: The End of Affluence: The Last Christmas in America.(TLCIA)

The article wasn't referring to the religious celebration; it was referring to the postwar concept of Christmas as the frenzied, exhausting year-end pinnacle of our one true secular faith, Consumption, a final orgy of buying and binging.

It is instructive to recall how the Federal government responded to unemployment, high inflation and rising budget deficits in the early 1970s: it began fudging numbers, manipulating data to mask the politically inconvenient realities of rising inflation, unemployment and deficits by playing switcheroo with Social Security Trust Funds, inflation data, etc.--games it continues to play in 2011 to cloak reality from the media-numbed public.

The market was not so easily fooled. The Bear market, reflecting the "real" recession, lasted 16 years, from 1967 to 1982. Now statistics are echoing that last great recession: rising prices for essentials, systemically high unemployment and stagnant wages while the corporate media and the organs of statistical manipulation (a.k.a. the sprawling, putrid public-private cesspool of the

Ministry of Propaganda) trumpet "the return of growth" and skyrocketing corporate profits.

(Today's propaganda: housing starts blip up due to statistical noise, and though starts are less than half pre-recession levels, this is heralded as "evidence" that "strong growth is back.")

The difference between the postwar boom of 1946 and the boom that followed 1982 is the last boom was based on the explosive expansion of debt. People didn't save and invest in productive assets; they went into debt to consume more and to become a "bigger" persona via the miracle of credit.

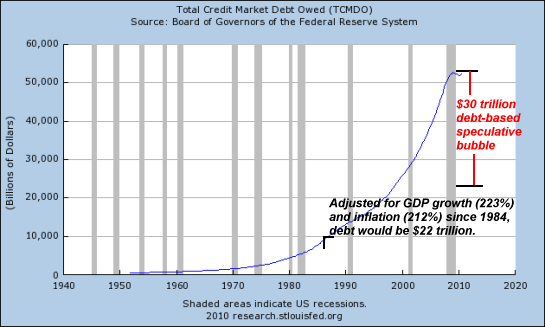

I often use this chart to make this point: if credit had expanded along with GDP, then we'd be considerably less indebted. Instead, it required a vast expansion of debt--some $30 trillion more than the rise in GDP--to fuel the 1982-2000 boom.

A funny thing happens when you depend on expanding debt to fund your consumption: eventually the cost of servicing your rising debt reaches the limit of your income, and you can't borrow any more, unless interest rates decline so you can leverage your income into higher debt.

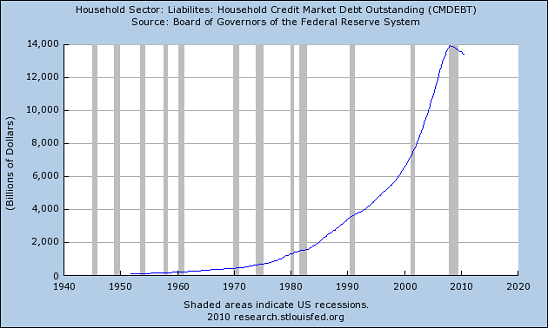

Here's a chart of household debt: that little reversal in debt expansion sent the economy into a tailspin.

Lowering interest rates extends the era of debt-based consumption, but it only puts off the inevitable crash when the ability to borrow runs out. Eventually the cost of servicing this lower-interest debt absorbs all your disposable income, and the borrowing skids to an abrupt stop.

Two other bad things can make this dominance of debt servicing worse: your income can decline, and the value of your assets can decline. In this unfortunate situation, you're ability to service your existing debts is crimped by a loss of disposable income, and you're paying for assets whose worth has fallen below the debt taken on to buy the assets.

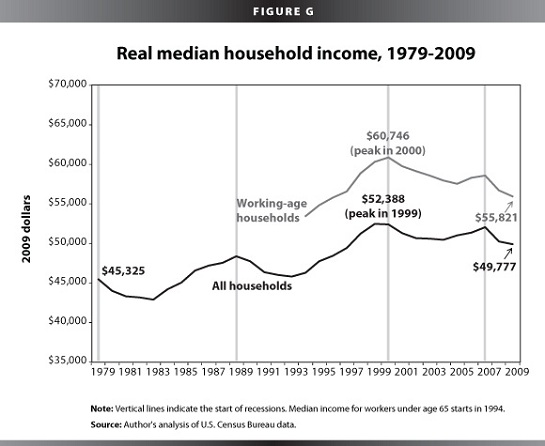

Income has declined significantly in the wake of the 2008 crisis/recession:

And here's the key asset of the middle class, housing:

This double-whammy of lower income and lower asset valuations is exactly where we are now. This is why the Fed's campaign to lower interest rates to zero and make it easy to borrow more have been as successful as pushing on a string; the economy is choking on over-indebtedness and overleveraging of stagnating income. There is no escape from this vortex except refusing more debt and writing off existing debt, wiping it off the balance sheets as an asset, driving lenders, banks and those holding debt as assets into insolvency.

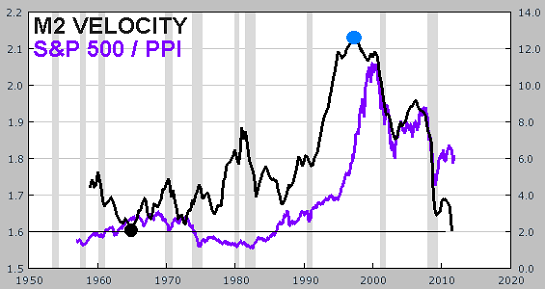

As we saw yesterday, the velocityof money--that is, money actually being borrowed and spent or invested in the real economy--has plummeted to zero.

We all know the 16-year recession/malaise back in 1967-1982 had a "happy ending": huge new oil fields were discovered in Alaska, the North Sea, West Africa and elsewhere, ushering in a renewed era of cheap, abundant petroleum. President Reagan "saved" Social Security for a generation by raising contributions paid by employer and employees, and he heralded a "lower taxes, higher permanent deficits" ideology that is now accepted as the norm: deficits don't matter, even when they reach the trillions, because our good friends the Gulf Oil Exporters and Asian exporters will buy all our debt forever, keeping interest low forever.

(And if they drop the ball, then the Federal Reserve will print money and buy the Treasury bonds. Sweet! We don't need any external buyers, just the Federal Reserve.)

Then the U.S. created and launched two revolutionary technologies which both created new wealth around the globe: the personal computer (microprocessor and cheap RAM) and the Internet (TCP/IP, Ethernet, and the commercialization of Tim Berners-Lee's World Wide Web with free browsers) spawning the generation-long boom of the 1980s and 90s.

Beneath the surface of this innovation-driven boom, however, the real engine of growth was debt and the financialization and globalization of the economy.

But when the wheels fell off that debt-fueled boom in 2000, the U.S. did not create a new engine of wealth: it opted instead for a devilishly insidious simulacrum of wealth: debt which rose at an exponential rate throughout the economy.

Borrowed money and phony financial legerdemain (mortgage-backed securities, derivatives based on the MBS, etc. etc.) from 2000-2007 created what I have termed a "bogus prosperity": no actual new wealth was created, only a brief and doomed bubble of debt-based housing valuations was inflated which followed the classic model set down by the Tulip Craze in Holland hundreds of years ago: insane boom, crushing bust.

We have to revisit the early 1970s for a reality check. In post-industrial America circa 1970, a huge surplus of food was grown by a mere 2% of the workforce. The cornucopia of manufactured goods was produced by about 20% of the workforce (hence the phrase "post-industrial"), and other than essential government services like the Armed Forces, police and the courts, the rest of society's work was either service-oriented paper-pushing relating to affluence (insurance), do-good selfless work (Peace Corps, churches) or leisure-related: entertainment, films, travel, amusement parks, stereos, etc.

This was not all fantasy. A friend of mine supported an entire house of hippies in late-60s Pittsburgh on his union steelworker job, and had plenty of money left to save for his trip to San Francisco. (As I recall, the rent for the big old house was less than $200 per month.) Hippies were the first ardent dumpster-divers/scavengers, driven not by poverty but by the idea that since that our society generated so much waste and surplus, why bother working?

As noted here many times before, the purchasing power of American wage-earners reached a plateau around 1973 and has been declining ever since.

One key point which is usually overlooked when comparing "The Last Christmas in America" circa 1974 and TLCIA circa 2011: the wealth distribution in the U.S. was much flatter then. CEOs of financial institutions did not earn $10 million each; there were no hedge funds with chiefs pulling down $600 million each (yes, that was the average "compensation" for the top ten fund managers at the hedgies' glorious peak), and even minimum wage ($1.60/hour in the late 60s, I know because my wage stub recorded it) bought far more goods (purchasing power) then than minimum wage does now.

Not only was gasoline cheap, but housing was far and away cheaper than it is today. Just about any G.I./Vet could buy a house with his/her V.A. benefits (3% down), and anyone else could scrimp and save for a few years and then buy a house for 2 or 3 times their annual wage at an interest rate around 6%.

Meanwhile, in TLCIA circa 2011, obscene "compensation packages" are defended as "free enterprise." Well, what did we have in 1973? Unfree enterprise? Amidst all the ideologically convenient defenses of heavily skewed "compensation," we have to admit that the dream of affluence combined with leisure was based on the presumption of society's wealth being distributed somewhat evenly, not by a Communist central state but by the "free enterprise" system and modest common-sense government regulation (limited work hours, minimum wage, etc.) which protected employees from the excessive exploitation of the late 19th century and early 20th century Monopoly Capitalists.

That dream seemed at hand in 1970. Now, after "the limits to growth" were mocked by those expecting ever larger oil fields to provide endless abundant cheap oil, we find that Peak Oil was merely put off a generation; there have been no new discoveries of super-massive oil fields since the early 1970s, and the supposedly abundant alternative petroleum sources like shale oil are horrendously costly to exploit, for they require vast quantities of energy (mostly natural gas at the moment) to be consumed to extract the oil.

Now we face a future which might well be called the End of Work for up to a third of the current workforce. Since agriculture employs about 2% of the workforce, industrial/factory production about 11%, essential transportation and essential government each a bit more, we have to ask: in an economy in which 70% of GDP is consumer spending, how many jobs are actually essential? How much actual wealth is being created/produced in the U.S. and sold overseas? Is giving people with Medicare coverage handfuls of costly and often ineffective medications and endless MRI tests actually creating wealth, or it mostly squandering it?

We might also ask: how much of the consumer economy is superfluous if wage-earners shift values and decide saving is more important than consuming? How many malls, storefronts, internet retailers, restaurants, fast-food joints, etc. can a newly-frugal economy support? How many dog-walkers, derivative salespeople, nail shops, carpenters, financial planners, realtors, etc. does an economy need if the FIRE economy (finance, insurance and real estate) is shrinking?

Based on the tremendous size of the service economy, construction, finance and government, I have estimated that 30 million jobs out of the current 139 million-strong workforce are superfluous. Many government positions are essential: police, meat inspectors, rangers, tax collectors, meter maids, etc., but as Mish so thoroughly illustrated in his detailed analysis of the California state budget ($120 billion or so), dozens of State agencies could be eliminated without any visible effect on the economy except to the wage-earners who lost their jobs.

If 20 million jobs disappear (7 million have already vanished since 2008), so do all the taxes those wage-earners paid; if 5 million homes go through foreclosure, the inflated property taxes the owners once paid will disappear, too. Once businesses close, it's not just wages which disappear: all the junk-fees governments levy disappear, too: the business taxes, the licensing fees, the permits, transaction fees, etc.

Does anyone think all these taxes and levies can fall and government employment will be funded by some other source? Yes, the Federal government can borrow apparently limitless sums at low interest rates; but soon, the surplus money which has piled up in exporters' accounts will be gone, and the endless borrowed trillions will actually start costing real money--money that will be diverted from government employment to pay the interest on all that wonderful debt everyone loved when they got a piece of it.

So how does a society deal with the End of Debt-Driven Consumerism, the End of Cheap Oil and the End of Work when it also means The End of Affluence, even for many of those with jobs? How does government deal with declining tax revenues and rising interest rates?

The death throes of the debt-based consumerist lifestyle are already visible beneath the glossy propaganda of "rising revenues this Christmas season." Those revenues were obtained by selling goods at below cost, in the absurd hope that income-strapped, over-indebted consumers would make profitable "impulse buys." As Mish has documented, the "impulse buys" are being returned even before Christmas to the tune of hundreds of millions of dollars.

The Fed is desperately attempting to re-inflate the debt bubble by lowering interest and mortgage rates and buying up all sorts of semi-toxic/impaired debt. What the Fed dreads is the reality we all feel and see: fear of the future due to diminished wealth and insecure incomes. If your assets have fallen in value, you feel poorer because you are poorer. Borrowing more at any interest rate will not make anyone feel wealthier.

People who fear their income may plummet due to layoffs or their hours being cut are not in the euphoric mood to borrow more, and banks which cannot dare to lose more money loaning to people who will default have cut off credit to millions of previously rabid consumers of debt.

Ask yourself this simple question: how much stuff could people buy if they could only spend surplus cash, after all their expenses and debt servicing payments were paid in full?

And let's not forget that much of what is purchased in this consumerist frenzy is needless, superfluous crap. My wife saves the most egregiously gift-buying-frenzy advertising circulars, and one from Bed, Bath & Beyond caught my eye.

There is no difference between this "1001 Best Gifts" from BB&B and a parody of consumerist excess. Hmm, how about an "executive standing valet" rack of wood and plastic for $99.99?

To make this poor-quality contraption, a forest somewhere in a Third-World kleptocracy was cut down and precious, irreplaceable oil was burned shipping the lumber to China and from that factory to the U.S. across 6,000 miles of Pacific Ocean.

We know this spindly piece of garbage will break in a matter of days, weeks or maybe if the owner is especially careful, months; then the legs will break loose of the base, the towel bar will pull out, etc. and the "we cut down a priceless rain forest to make this" piece of human handiwork will be put on the curb where a diesel-burning garbage truck will haul it to the landfill along with all the spoiled food Americans throw out.

The 16-bottle wine cellar/cooler from China (labeled Cuisinart for your consuming pleasure) for $199.99 might come in handy storing something once it's unplugged--but a cardboard box will probably do just as well.

I for one will not mourn the last debt-consumerist Christmas in America. Good riddance to the flaunting of borrowed money and the heedless, desperate purchase of valueless "goods" as gifts for an insolvent nation awash in too much of everything but common sense, integrity, gratitude, accountability and healthy living.

A previous version of this entry was published here last year.

| Thank you, Kevin K. ($20), for yet another most generous contribution to this site -- I am greatly honored by your longstanding support and readership. | | Thank you, Loren F. ($50), for yet another splendidly generous contribution to this site -- I am greatly honored by your ongoing support and readership. |