The real-world foundations of housing--income, debt levels, housing formation and jobs--are all weak or declining. How can housing "recover" if its foundations are crumbling?

The real estate industry announces the housing recovery is finally underway every year. 2012 is no different from previous years: various positive data points are duly cherry-picked (multiple offers are back in West Hollywood, sales are up year-over-year in Las Vegas, inventory is down, etc.) to back up the claim the "bottom is in" and the recovery in sales and prices is rock-solid.

We understand the industry's extreme self-interest in attempting to re-inflate housing, but let's begin with the obvious question: what's the housing recovery based on? The standard answer is of course "super-low mortgage rates, courtesy of the Federal Reserve."

But people need a sufficient income to qualify to own a house, regardless of rates, so let's look at income by age, and focus on the key homebuying ages of 25 to 44. The only age group whose incomes continued rising during the past five years is the over 65 cohort--the very group who is "downsizing" or selling their homes to live in assisted living. The key homebuying cohorts have seen their incomes plummet since the housing bubble popped.

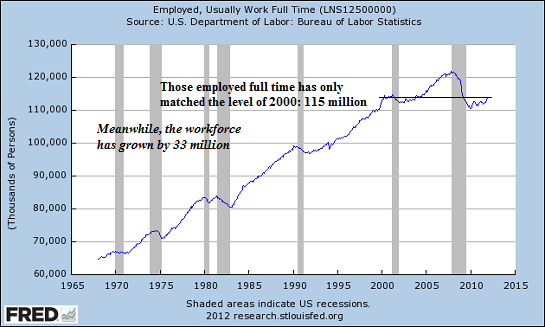

The official employment numbers are flim-flam because they include self-employed people earning $100 a year, people working one hour a week, temp jobs and contract labor, none of which supports the purchase of a house. The only jobs that enable home buying are full-time jobs with benefits. (If you have to buy your own healthcare insurance, that is so expensive it stripmines the household budget of disposable income. Only the top 10% can afford their own health insurance and a house.)

The number of full-time jobs has crept back up the level reached 12 years ago. Regardless of who you count in the workforce, tens of millions of people have joined the workforce since 2000, but the number of jobs that can support buying a house is unchanged.

There are 75 million households that own a home, about 65% of all households, so how many people who don't already own are qualified to buy a house?

This chart of "jobs plentiful less jobs hard to get" gives us some idea of the job market from the point of view of those seeking employment, and it's not exactly rosy.

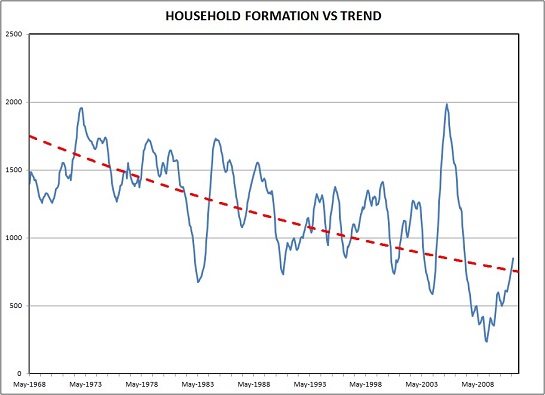

Given the poor prospects of full-time work, it's no surprise that household formation is trending down. It might seem that household formation correlates to population growth, but that is not the only factor: you need a decent income to afford an apartment or house of your own.

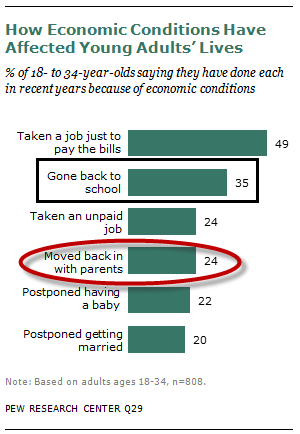

The future home buyers of America are staying in school to live off student loans and living in the basement/their old room at home.

Since the interest rates on student loans can be higher than mortgage rates, $100,000 in student loans will cost as much as a mortgage. Everyone with a mortgage-sized student loan will be unable to qualify for a mortgage unless they vault into the top 15% income bracket. Everyone below that high-income tier will have too much debt to qualify and too little income to service hundreds of thousands of student-loan/mortgage debt.

It boils down to one or the other: get student loans and forget owning a home, or avoid student loans and eventually hope to qualify for a mortgage. Few will be able to do both.

According to the Wall Street Journal, the Fed is worried about the "debt divide:"most people are over-indebted and cannot qualify for more debt, while those in the top income tier are scooping up cheap loans because their debt load is modest and their incomes are high.

The Fed's goal is to turn every American household into debt-serfs, and it's very success has it worried: now that it succeeded in turning 95% of households into debt-serfs, they can't take on more debt to fund their consumption. Only the top 5% can borrow, and a lot of them are wary of debt and won't borrow more regardless of the low rates offered by the "pusher," the Fed.

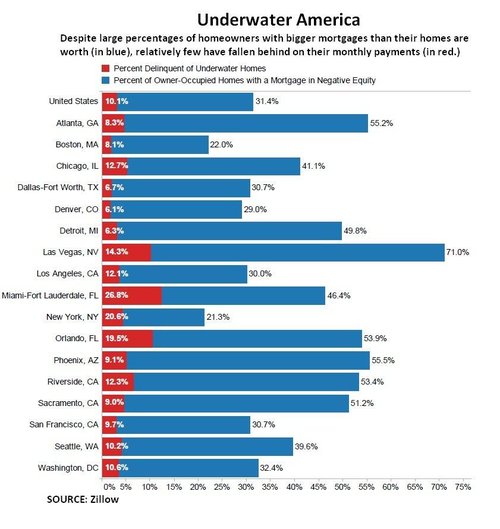

Millions of households are valiantly paying the mortgage even though their house is worth considerably less than the mortgage, i.e. they're underwater. The key take-away from this graph is the enormous pool of homeowners whose primary incentive to keep paying their mortgage is the hope that housing prices recover sharply enough to enable them to get out from underneath their mortgage. If that hope fades, then the incentives to keep dumping money into the mortgage for decades fades, too.

For some of these underwater owners, it may be cheaper to keep paying the mortgage than it would be to rent, so it makes sense to stay put. Others may want to keep their credit unimpaired so they can borrow money for other purposes. The key point here isthere is no equity to tap, and there is little equity being built. If the mortgage is $150,000 and the house is worth $100,000, then equity will finally appear when the principal loan balance dips below $100,000. If the owners have a standard 30-year mortgage, that principal reduction takes a long time.

In the meantime, the Fed's stealth campaign to inflate away the value of the dollar is eating away at the purchasing power of whatever equity is built. If the mortgage is finally paid off 25 years hence, what will $100,000 be worth in terms of real-world purchasing power?

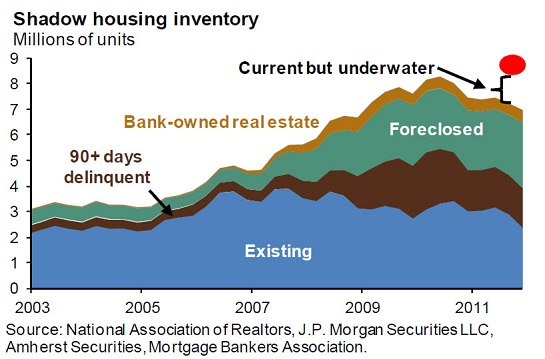

The real estate industry is crowing that inventory is declining, but this could be an artifact of lenders gaming the true number of impaired mortgages. Anecdotally, there is evidence that banks (unless required by state law to report all delinquent mortgages) are not reporting all delinquencies. There are myriad ways to "hide" delinquencies and houses that are not officially in the foreclosure pipeline.

If we place ourselves in lenders' shoes, we would play the same game, too: artificially restrict the inventory going to market so supply will fall below demand. That squeeze will boost prices, and the lenders will be able to off-load their off-market inventory over time at much higher prices.

But gaming a market whose foundations are crumbling is not a long-term positive.If the homeowner isn't maintaining the house or paying the property taxes, the lender is paying those expenses. It isn't "free" to hold a house off-market; even zombie houses cost a lot to own.

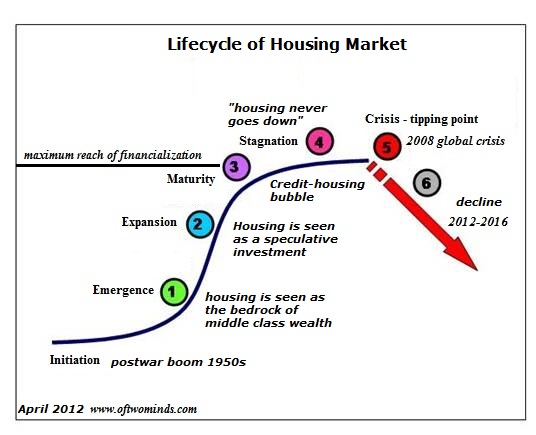

That suggests lenders' gaming the inventory cannot stave off the larger cyclical forces that are pushing housing along an S-curve of stagnation and decline. The duration and channel of the S-curve's decline is unknown, but if we review the factors that must be in place for people to buy houses--stable full-time employment, low debt loads and ample incomes--we find weakness rather than strength.

Yes, there is plenty of buying by investors, and we'll look at that tomorrow.

Resistance, Revolution, Liberation: A Model for Positive Change (print $25)

Resistance, Revolution, Liberation: A Model for Positive Change (print $25)

(Kindle eBook $9.95)

We are like passengers on the Titanic ten minutes after its fatal encounter with the iceberg: though our financial system seems unsinkable, its reliance on debt and financialization has already doomed it.We cannot know when the Central State and financial system will destabilize, we only know they will destabilize. We cannot know which of the State’s fast-rising debts and obligations will be renounced; we only know they will be renounced in one fashion or another.

The process of the unsustainable collapsing and a new, more sustainable model emerging is called revolution, and it combines cultural, technological, financial and political elements in a dynamic flux.History is not fixed; it is in our hands. We cannot await a remote future transition to transform our lives. Revolution begins with our internal understanding and reaches fruition in our coherently directed daily actions in the lived-in world.

| Thank you, Adam C. ($15), for your most generous contribution to this site--I am greatly honored by your support and readership. |

Resistance, Revolution, Liberation: A Model for Positive Change (print $25)

Resistance, Revolution, Liberation: A Model for Positive Change (print $25)