If an ossified, self-serving status quo refuses to adapt, collapse is the only way forward.

When everything's going great, nobody questions the nation's core institutions:they must be doing a great job because everything's going great.

The temptation to extend positive expansion to the moon is ever-present. Take Japan's "boost phase" of credit, banking and corporate expansion in the mid-to-late 1980s: pundits extended the soaring growth line and declared Japan, Inc. was going to own the world, or at least its most productive elements.

"Experts" fell all over themselves studying the structure and procedures of Japan, Inc., and hurried back to their home countries to copy Japan's success by copying its corporate structures, managerial culture and quality-control procedures.

Fast-forward 30 years. When one of Japan, Inc.'s leading corporations makes the news, as often as not it's the result of an accounting scandal in which corporate profits were grossly overstated for years as a matter of policy--a policy intended to mask the stagnation in the company's sales, product lines, competitive position and profits.

What happened to the often-copied, much-vaunted Japan, Inc.? Many observers see Japan's core problem as demographics: as its birth rate has fallen below replacement levels, the population of Japan is aging rapidly. Since young people start households and spend money, economic growth depends largely on the spending of young people rather than the declining spending of older people.

While a decline in the youthful demographic certainly impacts growth, this view overlooks the larger problem: Japan, Inc.--its educational system, government, banking and corporate sector--was optimized for the mode of production that existed in the postwar world from the late 1940s to the late 1980s.

Now that the Digital-Industrial Revolution is remaking the way goods and services are produced and distributed, the system that worked wondrously well in 1960 no longer aligns with the needs of this emerging mode of production.

In the 1980s, Japan's optimized-for-industrial-exports system reached its zenith, and many US pundits built careers predicting that Japan would soon eclipse the US in every economic and financial metric.

But the excesses of Japan's banking sector and the rise of new technologies that didn't lend themselves to gradual improvement and vertically integrated corporations disrupted the predictions of Japan's global dominance.

If you were able to go back in time to 1987 and tell the believers in Japan, Inc.'s inevitable dominance that by the 21st century Japan was no longer a leader in electronics, mobile phones, software and computers, they would not believe you.

This article on the failings of Japan's system of higher education is a window into the failings of Japan, Inc.'s culture, mindset and system of governance:Japan Gets Schooled (Foreign Affairs)

"Dismay rippled through Japanese society over the summer after the venerated University of Tokyo lost its number one ranking, falling to number seven, in the Asia university rankings published by the Times Higher Education of London.

The University of Tokyo (known as Todai in Japan) occupies a cultural space akin to Harvard, Princeton, and Yale combined in the United States. It is the launching pad for those who go on to run the country’s elite institutions. After the rankings slip, many Japanese felt that the country itself—not just its university—had taken a tumble.

Todai’s defrocking is emblematic of a broader problem. Japan’s educational system is failing to keep pace with changes taking place in Japan and in the rest of the world. Its drop in the rankings was due to funding cuts, poor research output, and an insufficiently global 'outlook.'

Optimized for an earlier industrial age, anachronistic educational institutions are struggling to adapt to a globally competitive marketplace for students, faculty, funding, and jobs.

No wonder that in interviews, educators and students use language frighteningly similar to that which a prisoner might use to describe his or her own predicament: 'trapped,' 'suffocating,' 'stuck,' and 'wanting to escape or sneak out.'"

Whenever I critique any aspect of Japan, people are quick to point out that it is still a wealthy, well-ordered society with many enviable amenities. But where does the wealth come from? It turns out Japan, Inc. earns vast sums of money from its overseas holdings--assets purchased in the heady days of yesteryear.

If we look at the nation's balance sheet and soaring public debt, it becomes clear that Japan is slowly eating its seed corn to maintain its staggering public spending deficits.

The essay's description of what's wrong with Japan's higher education is also true of Japan, Inc.: a system optimized for the mode of production of 1960 (integrated industrial production for the export market) will inevitably fail as that mode of production is replaced by another, much more demanding mode of production.

Every nation, developed or developing, faces the same core issues: either cling to systems optimized for a mode of production of bygone eras and stagnate, or adapt and optimize one's productive capacity and society to the new mode of production.

If you seek a data-based grasp of Japan's fiscal and financial decay, I recommend the following documents: the first is an easy-to-digest series of slides from an OECD study, the next two are detailed official Ministry of Finance reports in English, and the fourth one is an article describing the political resistance of the status quo in Japan to any real, systemic reform:

The key takeaway here is that decay can last for decades, enabling the status quo of the state and media to maintain the illusion that superficially all is well.As visitors and pundits never tire of exclaiming, Japan remains a wealthy nation where everything works wonderfully well--public transport, etc.--and the average lifestyle is enviable: long lives, good health, an abundance of consumer goodies, etc.

But this well-being has been maintained at a high cost. Social cohesion is fraying (beneath the surface, of course), birthrates continue to decline (and what does that say about a culture, that young women no longer want children?) and the signs of economic stagnation are visible to anyone who peeks beneath the hood.

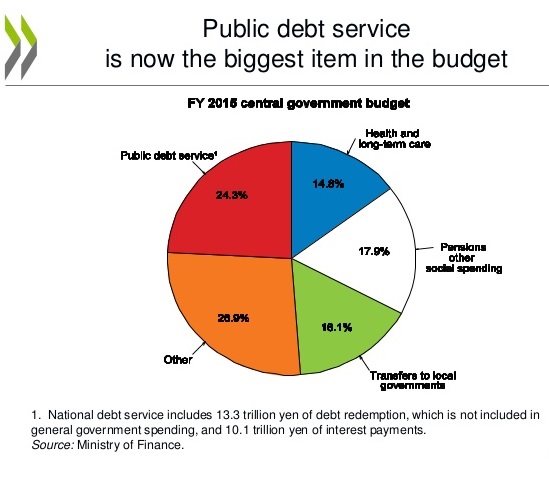

Decades of borrowing money in a futile attempt to avoid structural reforms has crippled Japan's fiscal future. Even at effectively zero rates of bond yields, Japan now spends roughly a quarter of its government budget on debt service--and servicing of existing debt now consumes 41% of all tax revenues.

Tax revenues only cover 64% of spending; 35.6% of the government's spending is borrowed.

These are staggeringly unsustainable policies, yet the status quo's refusal to accept fundamental structural changes dooms Japan to an unchanging trajectory of stagnation. Stagnation is never permanent, of course; eventually, erosion leads to collapse.

NOTE: Contributions/subscriptions are acknowledged in the order received. Your name and email remain confidential and will not be given to any other individual, company or agency.

Thank you, Jon O. ($10/month), for your outrageously generous pledge to this site -- I am greatly honored by your support and readership.

| |

Thank you, John D. ($30), for your splendidly generous contribution to this site -- I am greatly honored by your support and readership.

|