Where things will stand in three years in unknown. A little humility might serve us well, for it is indeed too soon to tell about a great many things.

Recent events call two quotes to mind, one from Napoleon Bonaparte and one from Chou En-Lai.

Napoleon: "Do you know what amazes me more than anything else? The impotence of force to organize anything."

Chou En-Lai: "It's too soon to tell."

The current backdrop is one of simplistic declarations presented as certainties because these are rewarded by the algorithms. Remarkably, few of those confidently declaring their implicit expertise ever acknowledge the limits of their own knowledge and the limits of the Ultra-Processed "facts" presented by the various interests seeking to control the context, narrative and agenda.

I reckon it fair to say that Napoleon was well-placed to survey the limits of force. That he is reputed to have observed "There are only two powers in the world: the spirit and the sword. In the long run, the sword will always be conquered by the spirit" makes sense in the context of the limits of the sword and other manifestations of force.

The phrase in the long run brings us to Chou En-Lai's "It's too soon to tell." Chou En-Lai (Zhou Enlai) was the People's Republic of China's first foreign minister and Premier, the statesman / diplomat who guided foreign policy while surviving Mao's tumultuous purges.

In the usual telling, while meeting with American officials during President Nixon's February, 1972 visit to China, Zhou was asked (in some tellings by Henry Kissinger, in others by Nixon) what he thought of the French Revolution, which occurred some 180 years earlier in 1789-1793.

Zhou's reply--"It's too soon to tell"--is presented as evidence of China's long game perspective that reflects China's long history and sagacious avoidance of rash judgments.

The real story is different but equally insightful. According to the American diplomat who was present during the famous conversation, the question was posed in a general sense, and since the participants in France's May 1968 general strike had contextualized those events in the language of the French Revolution and the 1871 Commune, Zhou interpreted the question as referring to the May 1968 uprising--a mere three-plus years before.

"It is too soon to tell"--the real story China fact of the day.

This doesn't detract from Zhou's sagacity. Events that are initially characterized by simplistic pronouncements often turn out quite differently from the expectations of those elevating superficialities to grandiose certainties.

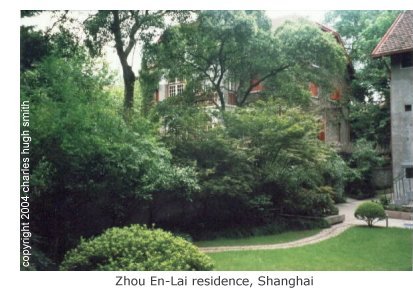

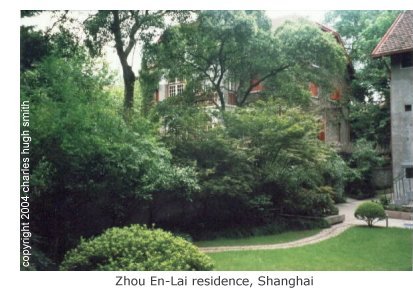

I first visited the Shanghai residence of Zhou Enlai in 2000 (photo below) when it was a lightly visited historical site that preserved much of the period's furniture and artifacts--including the battered suitcase Zhou had used on his overseas missions.

Numerous books--most recently, The Party's Interests Come First: The Life of Xi Zhongxun, Father of Xi Jinping--have documented the difficulties faced by loyalists such as Zhou in surviving Mao's mercurial purges and precipitous humiliations of senior officials in his inner circle.

Visiting Zhou's home in Shanghai's leafy French Concession humanizes a historical figure of the sort who who are all too easily turned into abstractions.

The same can be said of entire cultures and nations. What amazes me is the ease with which commentators implicitly claim sufficient expertise about a nation, region or geopolitical puzzle to make grand categorical statements about the situation without actually knowing any people who actually live in those places.

This profound ignorance of actual individuals' experience permeates the simplistic, catastrophically misguided tropes that pass for "policy" and "insight" in an era stripped of nuance and humility about the limits not just of force but of our own knowledge.

I'm amazed that pundits routinely claim sufficient knowledge to render judgments about complex cultures they know little or nothing about. In my experience, knowing a Syrian family, or families from Venezuela--and knowing full well that these individuals may not be representative of the entire culture or nation--offers an essential insight that abstractions and numbers cannot: these are real people being displaced, and real lives being upended or shattered.

Practically everyone is now an expert on China, it seems, yet few of those quick to make blanket statements actually have any Chinese friends who trust them enough to share their own experiences of the Cultural Revolution over a home-cooked meal.

This readiness to take abstractions as expertise should give us pause, because we've seen where this leads: arrogance masking abysmal ignorance and ideology replacing experiential knowledge with simplistic canards that can only generate errors of the most profound variety. Ideology of any stripe is no substitute for knowledge gained from long, careful study and personal experience.

A recent book traces out how supreme confidence in the abstractions of "management" and "statistical analysis" and in the powers of the sword led to the killing fields of Vietnam: McNamara at War: A New History.

We can discern the usual misplaced self-confidence and hubris of "the best and the brightest," of course, but we can also see the subversive weight of sunk costs, as withdrawing from a deployment of force that has already cost the nation credibility, treasure and lives is viewed as sending all the wrong messages of admitting error and weakness. And so the policy remains doing more of what's failed.

The fact that was always overlooked was the leadership's complete ignorance of Vietnam's complex history and culture. Safe and secure in a world of abstractions, it's easy to assume knowledge of abstractions is a satisfactory replacement for real knowledge. By the time this is revealed as catastrophically wrong, it's too late.

What's remarkable is how little humility about the limits of our knowledge is ever expressed by all those making simplistic, ideologically inspired blanket statements. There are uncertainties in what's being presented, and unknowns that are glossed over to project confidence and certainty.

Where things will stand in three years in unknown. A little humility might serve us well, for it is indeed too soon to tell about a great many things. A great many unexpected things can happen in three years.

My new book Investing In Revolution is available at a 10% discount ($18 for the paperback, $24 for the hardcover and $8.95 for the ebook edition).

Introduction (free)

Check out my updated Books and Films.

Become

a $3/month patron of my work via patreon.com

Subscribe to my Substack for free

NOTE: Contributions/subscriptions are acknowledged in the order received. Your name and email

remain confidential and will not be given to any other individual, company or agency.

|

Thank you, Tim C. ($7/month), for your monumentally generous subscription

to this site -- I am greatly honored by your support and readership.

|

|

Thank you, Jackson T. ($7/month), for your magnificently generous subscription

to this site -- I am greatly honored by your support and readership.

|

|

Thank you, G.F. ($70) for your superbly generous subscription

to this site -- I am greatly honored by your support and readership.

|

|

Thank you, Money designed for democracy ($70) for your splendidly generous subscription

to this site -- I am greatly honored by your support and readership.

|