What defines a "Good Economy"? Real advances in ownership of capital and the real-world resources an hour of labor can buy are within reach of the majority.

What defines a "good economy"? To answer this, we start with a second question: a "good economy" for whom? Economists turn to financial statistics to answer both queries, and this brings us face to face with the core difficulty with statistics: "money" is an overlay on the real world, and doesn't necessarily map the real world.

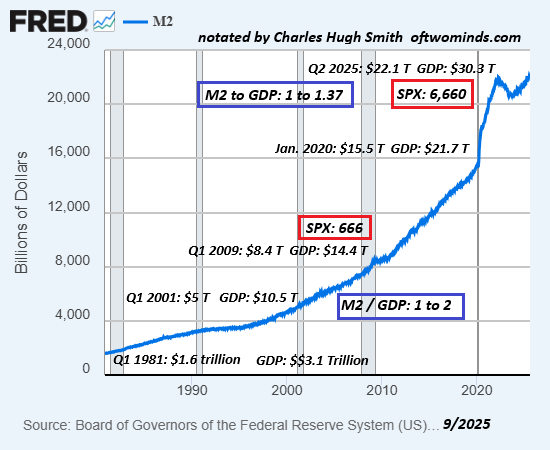

Economists measure "the economy" as a whole with GDP (gross domestic product), inflation, trade deficits or surpluses, money supply, the total credit/debt outstanding, productivity, and so on, but who's getting the real-world consequences--who's gaining ground and who's losing ground--is harder to determine.

Wealth as measured in money can be rising but this doesn't guarantee we're getting a higher quality of life. Much of real-world life can't be distilled down to dollars and cents, and so we ignore what's difficult to measure in favor of what's easy to measure: financial data.

I have long held that the only truly accurate measure of gaining or losing ground is how many real-world resources can be bought with one hour of labor. In other words, how many hours do we need to work to pay for shelter, healthcare insurance, childcare, college, food, utilities, transportation, etc.?

If we have to work more hours to buy the same resources that previously required fewer hours of work to buy, we're losing ground, regardless of statistics such as GDP, productivity, inflation, etc. If one hour of labor buys more real-world resources, products and services, we're gaining ground.

Put another way, the only meaningful measure of whether an economy is good or bad is social mobility, which has two components:

1. Whether we're gaining ground as defined above--what each hour of our labor can buy in real-world resources, and

2. Whether we're accumulating productive capital--assets that generate income and increase productivity--or not.

This is where the abstract world of economists touting higher GDP, net worth and income fails in a systemically consequential fashion: GDP can be rising, one's house can be gaining in value so our "wealth" is rising and our income can be rising, but if our labor buys less of the real world and we're just keeping our head above water paying for essentials, then all those "positive statistics" mean nothing.

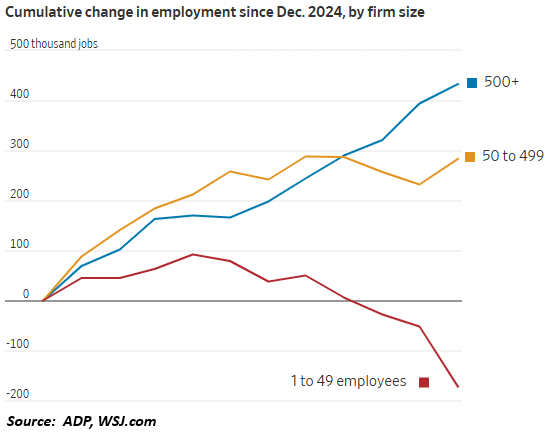

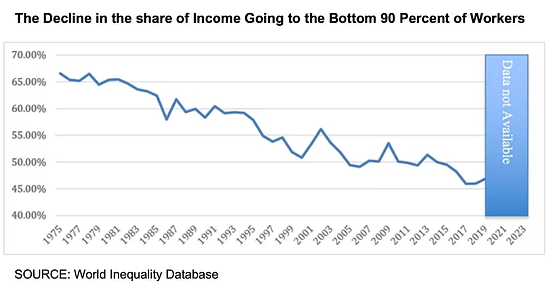

Social mobility describes the relative ease or difficulty of advancing not just one's income but one's ownership of productive capital. If only a handful of the bottom 80% can manage to claw their way into the top 20% as measured by ownership of productive assets, social mobility is broken.

If the core qualities of middle-class life are out of reach or demand extraordinary sacrifices and luck, social mobility is broken. These include a secure career / employment, healthcare, a home, and sufficient surpluses to accumulate productive assets, as opposed to gambling.

Economists have mastered Ultra-Processed Life, which is the substitution of artifice for authenticity. So we're supposed to accept that the auto that cost $24,000 a few years ago that now costs $40,000 is "equivalent" because it has more digital systems and air bags overlooks the reality that we have no choice but to buy what is being produced today: if we need a car, we now pay $40,000, and if this takes far more hours of work to buy, we've lost ground, regardless of "hedonics."

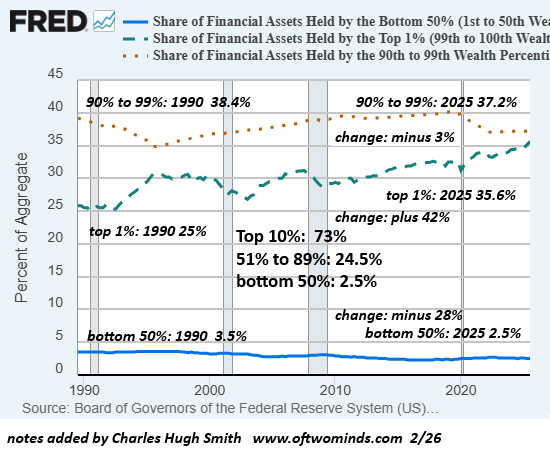

Italian economist Vilfredo Pareto found that the top 20% of households own about 80% of the land / productive wealth, and this ratio doesn't vary much. What varies is the dynamism of the flow of people into and out of the top 20%, i.e. social mobility both up and down.

When ownership of assets that produce income becomes concentrated above this 80/20 distribution, the social order / economy become unstable as social mobility decays and those in the top tier lock in their advantages.

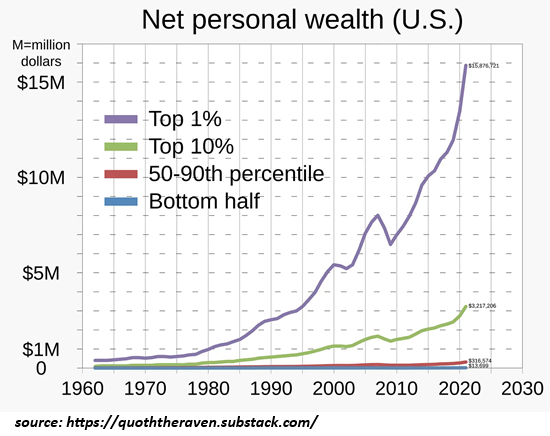

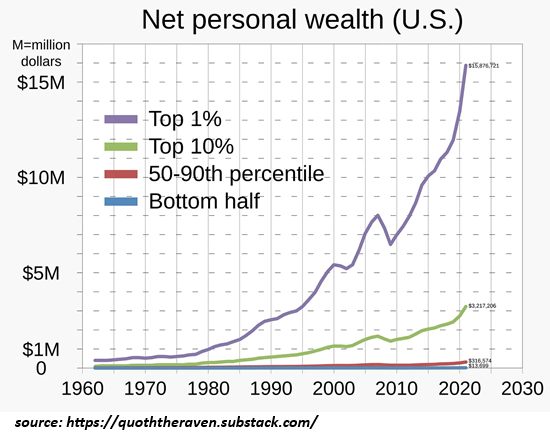

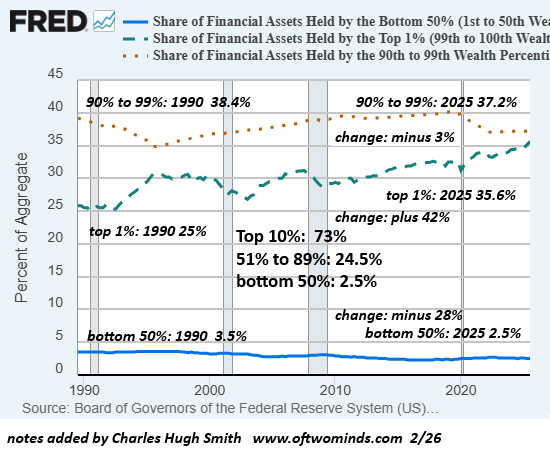

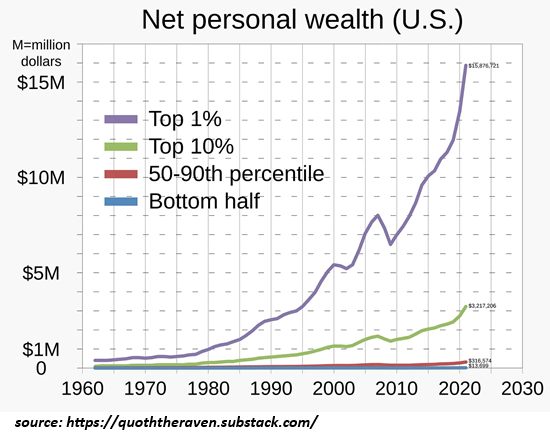

In the US, the top 10% now own roughly 3/4ths of all financial wealth. The "middle class" (those between the bottom 50% and the top 10%) own about 1/4th, and the bottom 50% own a signal-noise sliver: 2.5%. This distribution is more concentrated than 80/20.

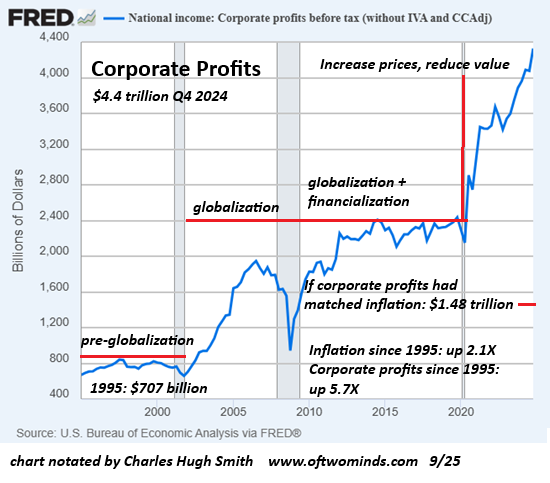

Here's another depiction of the same reality: a grossly imbalanced economy that favors the few.

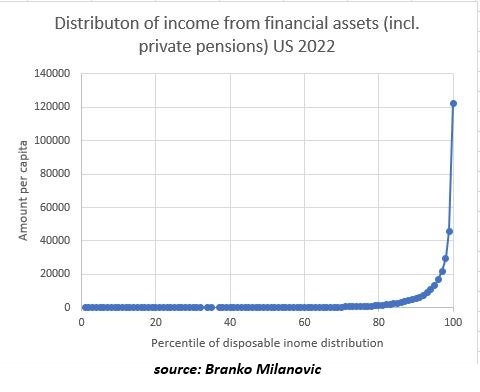

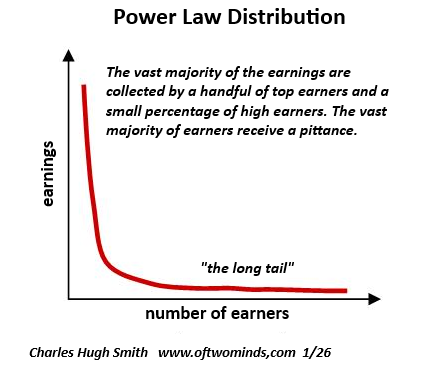

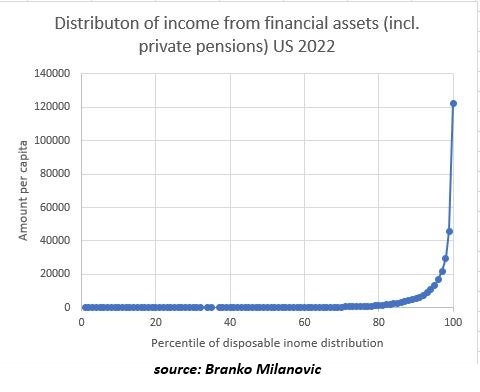

The income generated by capital is concentrated in the few at the top, a power-law distribution:

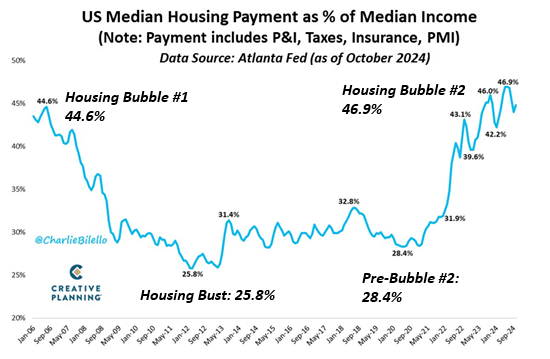

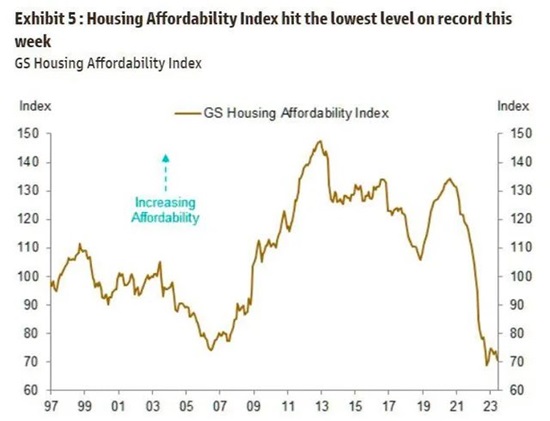

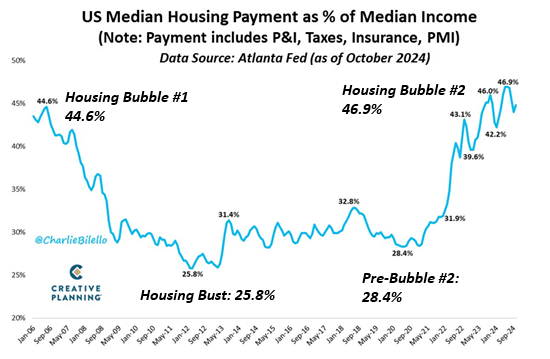

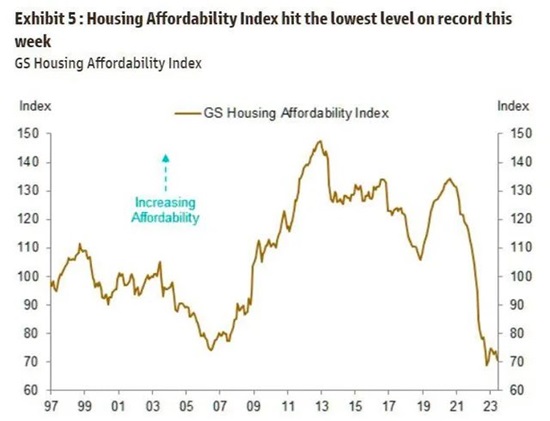

The cost of buying/owning a home is higher than previous eras, requiring far more hours of work to pay the mortgage, property taxes, home insurance, maintenance and other costs.

Housing affordability is at historic lows, meaning home ownership is out of reach of those who once could have bought a home without extraordinary sacrifices or family wealth.

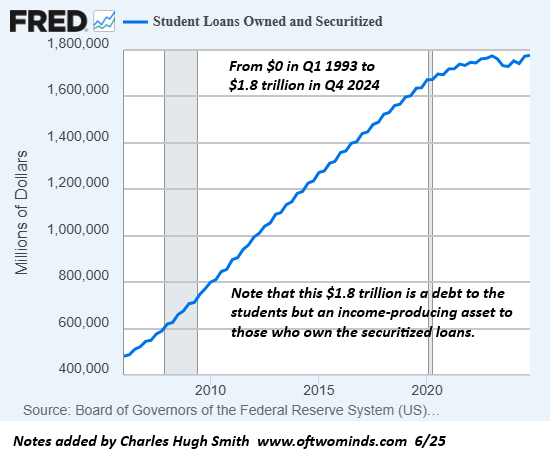

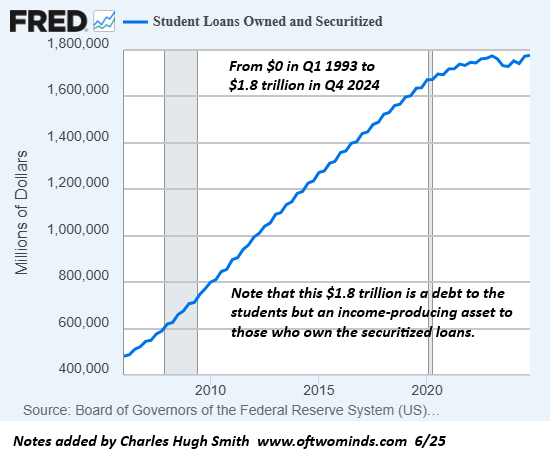

A college education did not require student loans a few decades ago. Now it requires debt-serfdom or wealthy parents: the number of hours needed to "buy" a university education has skyrocketed.

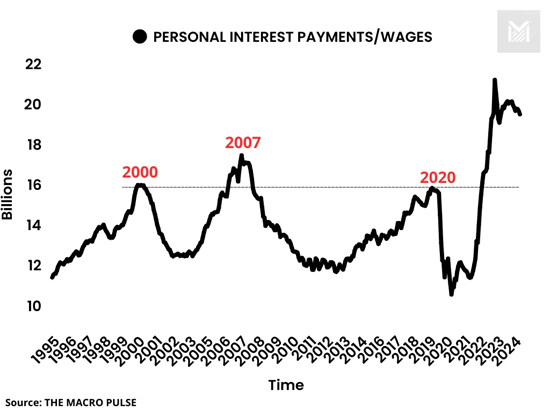

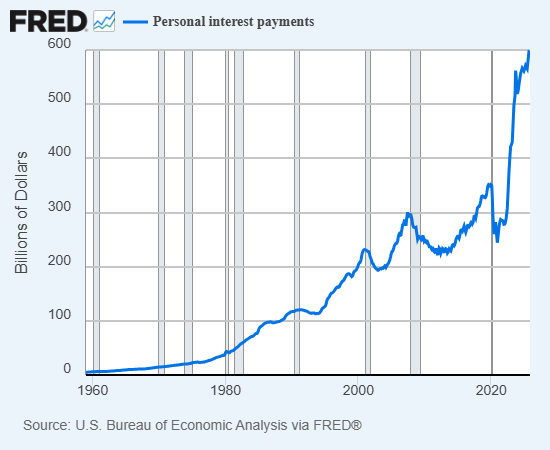

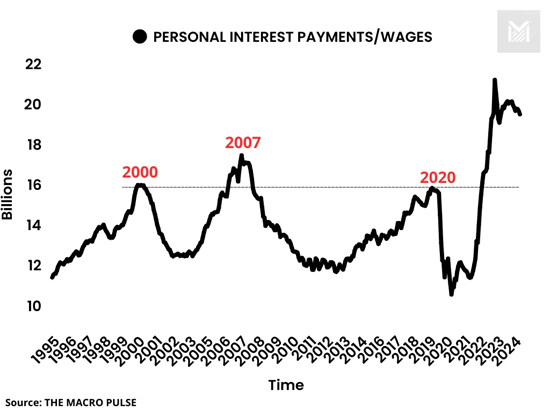

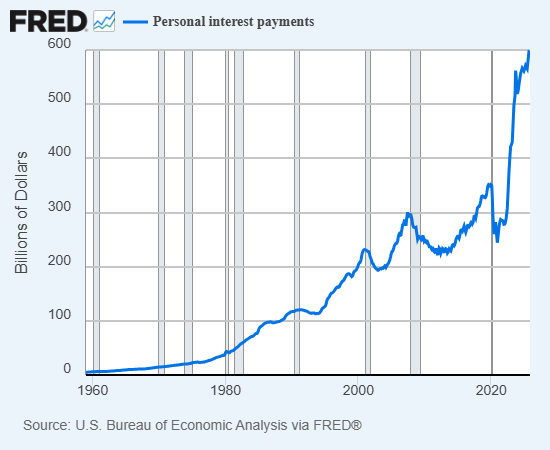

As debt becomes the norm to afford a middle-class quality of life, an increasing share of wages is devoted to debt service/interest. Recall that every student loan and mortgage is a debt to the borrower but an income-producing asset to the owner of the loan.

The income spent paying interest is income that cannot be set aside to accumulate productive capital.

An economy where people are increasingly relying on gambling as their last-ditch means to secure a future that is less precarious than the present is not a "good economy" except for the top 10%. And to the degree their wealth is also a gamble placed in a central-bank casino, the precarity of all this wealth is masked by the artificial "goodness" of statistics that reflect artifices rather than the real world.

What defines a "Good Economy"? Real advances in ownership of capital and the real-world resources an hour of labor can buy are within reach of the majority. In an era of rising precarity and receding social mobility, many will settle for Not Losing Ground.

My new book Investing In Revolution is available at a 10% discount ($18 for the paperback, $24 for the hardcover and $8.95 for the ebook edition).

Introduction (free)

Check out my updated Books and Films.

Become

a $3/month patron of my work via patreon.com

Subscribe to my Substack for free

NOTE: Contributions/subscriptions are acknowledged in the order received. Your name and email

remain confidential and will not be given to any other individual, company or agency.

|

Thank you, Good Journal Capital ($75), for your massively generous subscription

to this site -- I am greatly honored by your support and readership.

|

|

Thank you, SDC ($7/month), for your magnificently generous subscription

to this site -- I am greatly honored by your support and readership.

|

|

Thank you, Bruce L.M. ($60) for your superbly generous subscription

to this site -- I am greatly honored by your support and readership.

|

|

Thank you, Tap ($7/month) for your splendidly generous subscription

to this site -- I am greatly honored by your support and readership.

|

Read more...